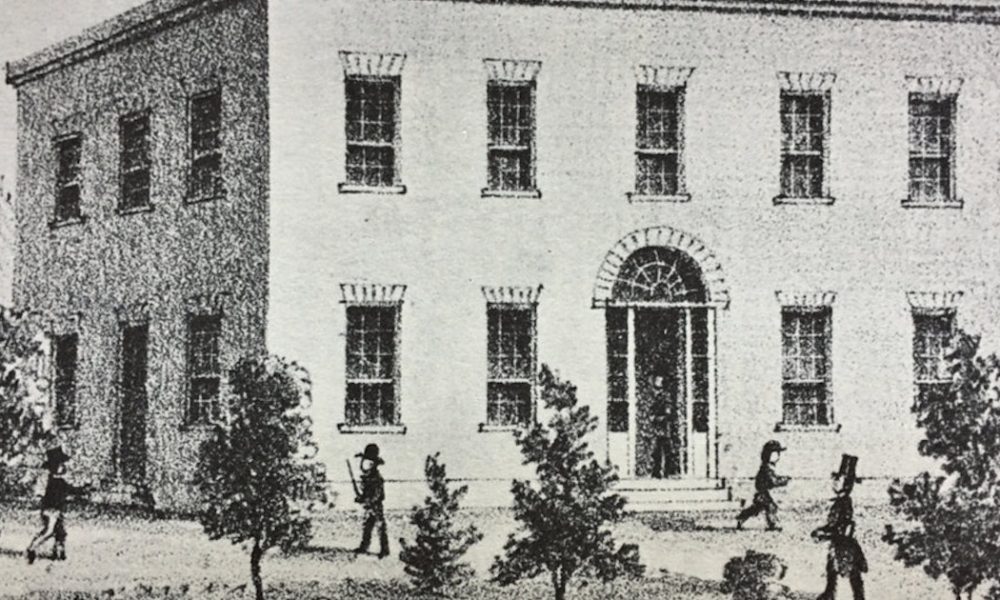

The fireproof stone building which was under construction throughout the short life of the college. PHOTO PROVIDE/Oregon Historical Society

The fireproof stone building which was under construction throughout the short life of the college. PHOTO PROVIDE/Oregon Historical Society

The University of Oregon, as most alumni can tell you, was founded in 1876 as the flagship of Oregon’s university system.

But the channels the university project flowed through, with the enthusiastic support of the Eugene community, had already been cut years before by a short-lived institution called Columbia College.

Columbia College collapsed a few months before the Civil War broke out, after the college president, a staunch pro-slavery man, tried to murder the editor of a local Abolitionist newspaper, and then jumped bail and went on the lam.

But while it lasted, the college made up a huge part of the Eugene City population – about a quarter of the town’s residents were students. And it gave all the residents of old Eugene City a taste of what it was like to be an important regional center of learning – a taste that they would remember, 15 years later, when it really mattered.

Columbia College was initially chartered by an offshoot branch of the Presbyterian Church, but it was intended to be a real college, not just a training program for ministers. Part of the financing for the college was an innovative and effective scheme reminiscent of the punch cards used at Dutch Bros. coffee kiosks: Scholarships were offered at $100 each, and anyone who sold nine of them got one for free. Anyone who wanted to could earn one of those free scholarships by selling nine to neighbors and friends.

This marketing campaign turned out to be unusually effective not only in ”putting butts in seats,” but in making the new college a surprisingly diverse place. Students from all over the expansive Oregon Territory signed up, as well as a number from outside the area. By the fall of 1856, when the college was scheduled to open, 52 pupils were signed up, both men and women.

That number would rise steadily over the next few years, peaking at around 150 students – and in the process, totally dominating the town of Eugene City, whose population at the time was around 500. Columbia College would have more than its share of challenges to overcome over its short run, but lack of students was never one of them.

The first of those challenges came less than a week after classes started. The first day of classes started two weeks late because the building wasn’t ready for students yet; but on Nov. 20 – literally the very first Thursday after classes started – the freshly built building caught fire and burned to the ground.

College President Enoch P. Henderson promptly proclaimed it the work of an arsonist. This was probably untrue, but it hinted at the real problem Columbia College would be facing throughout its run: Politics. Henderson was an abolitionist, and so were most of his associates on the board and in the classroom; but many others were pro-slavery. Passions were high and mounting on both sides. By the time the school was founded, the tension between the two factions had already gotten bad enough that they were accusing one another of arson. They would only get worse as the years wore on.

College board secretary, J. Gillespie reassured the community not to worry; the show would go on. And so it did, with the loss of only one day of classes, in a rented house nearby.

Meanwhile, work continued on a new building – one intended as a temporary structure, to tide them over while a deluxe fireproof building made of sandstone was prepared. This building was ready for them when the 1857 fall-term session started. It lasted longer than the first building had – but that wasn’t saying a whole lot. In any case, the whole works went up in smoke on Feb. 26, 1858.

Again, Henderson claimed it was arson. This time, though, he was more likely to have been right. By 1858, a lively tug-of-war was under way between the pro-slavery and abolitionist parties. The pro-slavery activists had, the previous year, launched an ongoing campaign to take over the college board. They failed twice, in 1857 and 1858, and in 1859 tried and failed to have Henderson’s salary reduced; but after that he decided to take the hint and tendered his resignation. Without him there to galvanize the Abolitionist forces, the pro-slavery people easily took over, and quickly consolidated the college board to push the remaining abolitionists out.

Henderson was replaced as college president by a man named M. Ryan. Ryan was a staunch pro-slavery Southerner, and wrote several articles for the Pacific Herald under the pseudonym ”Vindex.” In them, he blasted the abolitionists.

Those editorial broadsides were answered in The People’s Press by one of Ryan’s own students, H.R. Kincaid – later one of Eugene’s most prominent citizens – writing under the pseudonym ”Anti-Vindex.”

Ryan was so incensed by Kincaid’s work that on the evening of June 22, 1860, he tried to kill People’s Press editor B.J. Pengra, whipping out a pistol and firing at him with it.

”The ball was not well aimed,” the Oregon Journal’s reporter recounts, ”and missed Pengra, who sprung upon Ryan, bore him to the ground, and choked him till he was black in the face, when some bystanders interfered and separated them.”

Pengra immediately filed charges against Ryan for attempted murder, and Ryan had to post $1,500 bail. He then promptly jumped bail and skipped town.

After that, Columbia College was basically done. It straggled on for a few more months; but a combination of the brewing American Civil War and a hefty judgment stemming from a lawsuit filed by former president Henderson (whom the new pro-slavery college board had attempted to stiff for a semester’s pay) forced it to declare bankruptcy and dissolve.

But just before that happened, the students finally got to move into the new fireproof stone building – the permanent structure that had been under construction since the first building fire. It wasn’t quite finished and ready yet, but the students were, so some classes were moved into it. And although it didn’t catch fire, the college’s building jinx was apparently still going strong.

According to ex-president Henderson’s niece Kate, ”one stormy day there came a creaking and rattling overhead, and the timid ones among us were greatly frightened, supposing the whole building was about to fall upon us, but our fears were quieted as it was ascertained that it was only the tin roof loosened from its fastenings, and being rolled up in a scroll was literally thrown from the building and rolled off down the hill.”

Perhaps it just wasn’t meant to be.

From the first day of classes to the day the roof blew off, Columbia College was only open for four years. But during its short run, the College had a surprising impact on the intellectual development of frontier Oregon – which must have had a lot to do with the sheer number of students who came.

Among those students, the most well known name nationwide was that of Cincinnatus ”Joaquin” Miller, the future ”Poet of the Sierras,” who attended classes there for several months. Miller would later claim Columbia College as his alma mater, writing in later years that he ”graduated summa cum laude” from Columbia; but, as historian Perry Morrison delicately puts it, ”It is very difficult to separate fact from poetic license when one deals with the career of the Poet of the Sierras.”

Other important names on the student roster include J.J. Walton and J.M. Thompson, two of the primary movers in the establishment of the University of Oregon 15 years later; and future U.S. Congressman J.D.H. Henderson, the college president’s brother, who came to Eugene specifically so his children could attend Columbia College, and later supplied the 20-acre parcel of land on which the U of O would be built.

But Columbia College’s influence goes beyond the names of its students. It basically gave the rough-cut backwater settlement that was pre-Civil-War Eugene City a taste of life as a Mecca of letters, and the citizens clearly liked it.

”The people here, many of whom had been its students, never forgot in the struggles of later years that this place had once been an important center of learning,” writes historian Joseph Shafer in his 1901 article. ”To this fact I believe may be attributed much of the ardor shown a decade and more later in the pursuit of the university project.”

Fortunately, when the real university project got under way, it took care not to hire any prickly Southern gunslingers as university presidents. Speaking of which, ex-president Ryan was never caught and never heard from again. A probably-true rumor claimed he’d fled back to old Dixie, and when hostilities broke out a few months later joined the Confederate Army.

– – – – –

(Sources: ”Columbia College 1856-60,” an article by Perry D. Morrison, and ”Survey of Public Education in Eugene,” an article by Joseph Shafer, published respectively in the December 1955 and March 1901 issues of Oregon Historical Quarterly; archives of the Oregon Statesman, 1860).

– – – – –

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. His book, ”Heroes and Rascals of Old Oregon,” was recently published by Ouragan House Publishers. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.