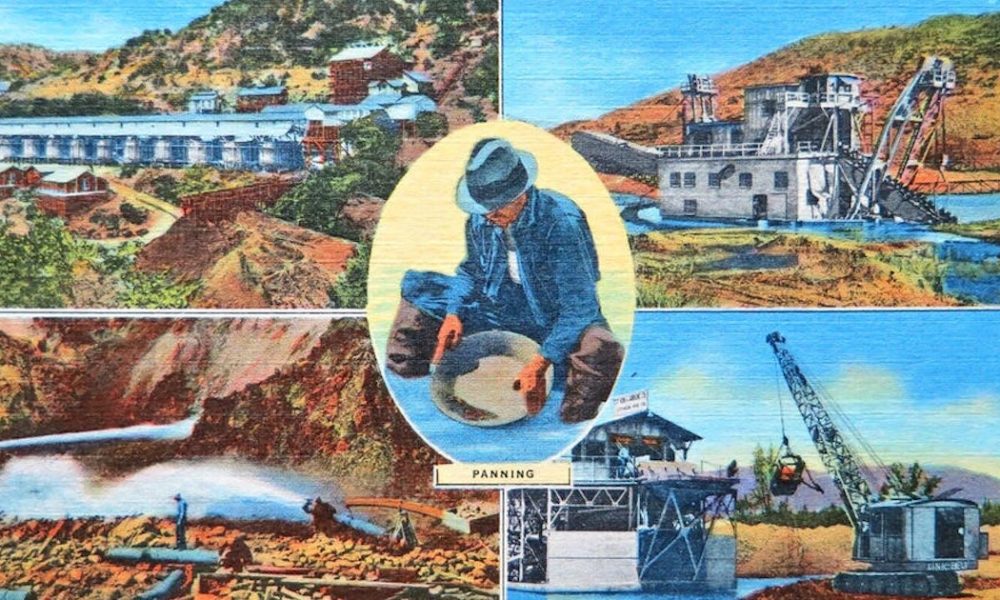

An early-1900s vintage picture postcard shows five different methods of mining gold: quartz stamping, hydraulic, dredging (with an old-school bucket-line dredge), use of a doodlebug, and panning. Postcard Provided

An early-1900s vintage picture postcard shows five different methods of mining gold: quartz stamping, hydraulic, dredging (with an old-school bucket-line dredge), use of a doodlebug, and panning. Postcard Provided

In the years that followed the American Civil War, the American federal government was gasping for cash.

The war had been largely financed by borrowing huge sums of money from abroad, mostly from England. There weren’t many other options. America’s two main export crops, cotton and tobacco, were products of the South – which is why President Lincoln spent so heavily to throw a blockade around Southern ports.

By the time it was over, the Union government was having serious heartburn over debt service. And, of course, its revenue-generating options were fairly limited in those pre-income-tax days.

And yet, on the other side of the country, hordes of scruffy ruffians digging in the dirt and wading in the streams of Oregon and California were pulling a vast fortune out of the public domain – and keeping it all, giving not even a nod to the government that was the actual owner of the land that was making them so rich.

To these Eastern politicians, it didn’t seem right. Here was Uncle Sam, which owned the land all this loot was being picked out of, getting absolutely nothing while a bunch of squatters swarmed over it, picking the carcass clean.

And to make matters even more open-and-shut for them, it was well known that the majority of miners in the gold fields were of Southern origin, and most of them had pulled hard for the Confederate cause. So, to the way of thinking of men like Rep. George Julian of Indiana, not only were they thieves, but rebels and wartime enemies to boot.

The solution? To seize the gold fields by military force, and either exploit them via government-owned mining operations or turn them over to the nation’s creditors as partial payment of the war debt.

Indeed, those European creditor powers were already massing troops on the Mexican and Canadian borders, ready to surge across the line and start seizing (or helping to seize) mines and gold fields the instant they got the signal. And a strong and growing group of members of Congress from Northern and Eastern states stood ready to give them that signal.

The support for this position was building rapidly in the months after the war ended. So Senator William Stewart of Nevada moved to preempt it. In 1866, he introduced a bill that would lock in the status quo and protect miners and future miners from the threat of government expropriation.

”The mineral lands of the public domain … are hereby declared to be free and open to exploration and occupation by all citizens of the United States,” the bill announced, and went on to outline miners’ rights to build access roads, dam streams and build structures to help them in their exploration and occupation.

Stewart and his supporters believed that the injection of billions of dollars into the U.S. economy since 1849 had been so beneficial that changing miners’ incentives risked killing a goose that was reliably laying golden eggs for everyone.

Then, too, seizing mining operations after the hard, risky work of prospecting, accessing and excavating was done didn’t seem fair to his Western sensibilities. The government represented the people, not the politicians entrusted with it; and it hadn’t done a thing to exploit the gold fields except stand aside and let the miners do their thing. For it to step forward now and, as it were, high-grade everyone’s claims just because it could – that would be morally insupportable.

The opponents of the bill may have underestimated how much interest there was in gold mining out West – and how much the fairness question weighed. Following a bitter fight, Stewart’s bill passed into law. It was refined and expanded over the following six years, finally being completed and codified as the General Mining Act of 1872.

Under it, individuals are granted a literal ownership right in their claims so long as they are being actively worked. That’s why miners are legally empowered to hang ”no trespassing” signs on their claims: There is very little difference between a miner’s ownership interest in an active mining claim and a suburban homeowner’s ownership interest in her/his own back yard.

Although it mainly just codified existing practice, as a matter of legal doctrine this was a revolutionary and controversial thing at the time. It was the first time any nation had simply handed over its mineral wealth to whoever wanted to claim it and exploit it.

According to the 1917 Pan-American Scientific Congress, ”It was the first instance where a sovereign broke away from the old regalian right and voluntarily ceded to her citizens as a gift all her mineral wealth on the sole condition that the citizen should go out and possess it.”

Moreover, according to Jackson, it was also the first time in U.S. history that de novo property rights were granted to single women. The law didn’t say what gender the miner had to be. And in consequence, lots of women who didn’t want to deal with husband husbandry took advantage of this, and went into the gold fields to work their very own mining claims.

”This is not just a mere license to mine, but in fact, a grant of unique property,” Jackson wrote. ”The Mining Law was written this way for the simple fact that it was the ideology of its writers that minerals are a critical portion of our infrastructure and that if average people were given the opportunity to own and develop 20 acres of mineral land, that it would benefit the nation as a whole. History has proven that their theory was very much correct.”

(Sources: ”Gold Dust: Stories of Oregon’s Mining Years,” a book by Kerby Jackson published in 2011 by Six Guns Press; ”Beach Placers of the Oregon Coast,” a report published in 1934 by J.T. Pardee for the U.S. Department of the Interior)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. His book, ”Heroes and Rascals of Old Oregon,” was recently published by Ouragan House Publishers. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.