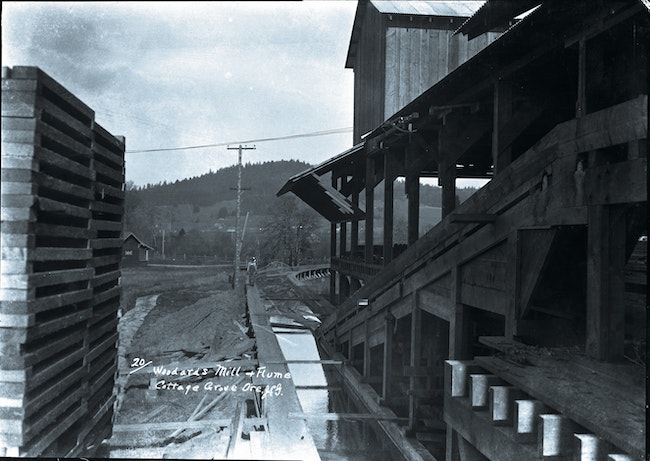

This old postcard provides a broad view of the famous Woodard Flume. Casey Woodard, grandson of Walter W.A. Woodard, confirmed this is the Camp B Woodard Mill in Hebron (now underwater). He noted that the butte in the background is used to anchor the dam for Cottage Grove Lake. The Hebron school house is also visible in the distance. PHOTO COURTESY OF COTTAGE GROVE HISTORICAL MUSEUM

This old postcard provides a broad view of the famous Woodard Flume. Casey Woodard, grandson of Walter W.A. Woodard, confirmed this is the Camp B Woodard Mill in Hebron (now underwater). He noted that the butte in the background is used to anchor the dam for Cottage Grove Lake. The Hebron school house is also visible in the distance. PHOTO COURTESY OF COTTAGE GROVE HISTORICAL MUSEUM

Editor’s note: This is the third of a three-part series. Read part 1 here and part 2 here.

Walter “W.A.” Woodard was the last of his breed, a large-scale independent lumberman who had worked his way up from cutting cordwood to running one of the most efficient and modern mills – which he completely owned and directed. His history follows that of the changing technology in the timber industry. In his lifetime, W.A. saw the use of dray animals, hand tools, steam donkeys, and flumes give over to diesel trucks, chainsaws, and more modern methods of turning timber into lumber.

He was an agent for many of those changes here, partly due to his natural talent for observing and constantly tinkering with his operations, but largely from his vision and shrewd business decisions. Even as a kid he was nicknamed “giant” not from his stature but by the outsized ideas he often had. Possessing a genius level of mechanical aptitude, Woodard was never content with the status quo. Grandson Casey Woodard shared a story he heard from his grandmother Dutee:

“At night when W. A. was watching television, he would often be drawing and doodling on a pad. Out of these sketches would emerge a solution to some problem with machinery or operations at the mill.”

W.A. Woodard, “Rugged Individualist”

W.A. Woodard, “Rugged Individualist”

‘Green Gold’

The Woodard Family, parents Ambrose and EllaJane Young Woodard with 8 kids, arrived in Cottage Grove in 1900 from Wheaton, Ill. It was a time for opportunity, the Bohemia and Blackbutte Mining Districts were still working and the new “green gold” of timber was heating up. Ambrose, two older sons, and W.A. started out cutting firewood for the railroad to power locomotives, eventually branching out into piles and poles for PT&T. The hard work paid off with Woodard Sr. saving enough money to join with partners to form Coast Fork Lumber company. At the mill site Woodard, being capable with his mechanical sense and good hands, able to fix any of the mill machinery, worked his way up to be foreman.

The mill just south of Cottage Grove (Riverwalk nowdays) was sold to J. H. Chambers in 1910. At the time it was the largest and closest mill to town. When it burned down a year later, W.A. was hired to build it back then stayed on to become foreman.

After recovering from an accident he resumed his traveling, building and working in mills all the while gathering ideas on how to improve efficiency and safety. On one of these trips he ended up in San Francisco and made one of his first big profitable deals. Noting that used wire cable sold for $50/ton in California oil fields and could be sold for much more in Oregon shipyards and timber operations, he convinced J.H. Chambers to front him capital to buy cable which they could then sell at $250/ton. Both realized a nice profit, Woodard immediately purchased 160 acres of timberland near London with his share. This was to be a fortuitous decision in many ways.

Before a year had passed W.A. was approached by Harold Bradley, an agent for N.B. Bradley & Sons, a Bay City, Mich., lumber company. They wanted to buy Woodard’s timberland (at a nice profit) but more importantly wanted W.A.’s know-how. With his expertise in mill construction and the company’s considerable financial resources it was the birth of Woodard’s massive and successful enterprises. They set up a mill in London known as “Camp A.” Incorporating as W.A. Woodard Lumber Company in 1925, ending his financial obligations to the Bradley firm, though their partnership lasted many years more and together they were able to weather many economic downturns.

Woodard’s London “Camp A” mill with crew. PHOTOS COURTESY OF Woodard Family Archives.

Woodard’s London “Camp A” mill with crew. PHOTOS COURTESY OF Woodard Family Archives.

The lumber industry is inextricably connected to the general economy. So goes the one, so goes the other. In the 1921 post-war recession, many mills were forced to shutdown, including Woodard’s. W.A. used this opportunity to rethink and retrofit so that when things picked up Woodard’s mill was ready to roll with a greatly increased production. During the Great Depression Woodard often paid payroll out of his own pocket and at other times took no salary to keep the operation moving during the rough patches of the timber trade, knowing better days were ahead.

Moving cut logs was an evolving process. In the early days roads were few and in poor condition. Log and tie drives down the rivers was how logs got to the mill or to a railroad siding. As roads were added and trucks improved the day of motorized logging was dawning. Before trucks really took over Woodard built one of the longest log flumes in Oregon. Approved in 1921, the eight mile flume was well researched by W.A. himself, who traveled to observe other flumes to study the terrain, obtain easements (reported to cost $40,000), and tangling with Lane County (it crossed the county road six times).

The Flume

The flume, a V-shaped trough of planks with cedar supports usually ran 4 to 7 feet off the ground with the highest point being 20 feet. Construction began in January 1922 and was done five months later. There was a walk way, a 12-inch plank, called the toe board, where tenders patrolled their section looking for jams. Locals were known to hitch a ride downstream on log rafts then walk home after their business in town.

Containing over a million board feet of lumber and using 325 kegs of nails the flume could transport up to 600,000 feet daily of rough cut lumber from the London Mill to near Latham. Despite its effectiveness, the log flume fell to a different sort of progress. Nine counties that shared the riches and floods of the Willamette River system voted in 1933 to establish the Willamette Valley Project. The Flood control act of 1936 directed further resources towards ending the frequent floods that bedeviled valley inhabitants. The dam that forms Cottage Grove Lake today began in 1940 and eventually covered the settlement of Hebron completely. Included in the lake’s path was Woodard’s London and Hebron mills – and flume. Many Hebron residents were descendants of original donation land claim settlers, such as Geers and Shortridges, and faced losing their family’s legacies of generations of improving the land.

Woodard razed his mills ahead of the rising waters and moved all his operations to Latham. By December 1940 he was testing his new setup. The new mill was compact and featured many innovations; band saws, a shotgun feed carriage with all of the dogs and adjustments operated electrically. After a few tests the mill shut down again for adjustments. This is the mill currently operated by Weyerhaeuser. What is known as Weyerhaeuser Road today was a private logging road W.A. established to move logs when his flume was forced, by the dam construction, to shut down. Locals salvaged lumber from the flume for themselves.

Demanding, but fair

He expected a lot from his employees and insisted they work hard to earn their pay. He had the policy “Hire the best possible workers, pay them well (his wages and payroll were the highest in town) and take good care of them so they stick around.” This policy helped delay introduction of unionization at Woodard’s operations. But there were no second chances, if a man was fired, that was it.

Woodard had the reputation among his crew of being demanding but fair. He figured he knew what a working man needed having worked hard all of his life in all phases of lumber operations. Many of his employees were happy enough to spend their entire careers working for Woodard, such as the Dugan brothers and many others.

Sons Carlton and Alton were introduced to the business the same way W.A. had been, from the bottom. Carlton started off cleaning chips and sawdust out of the conveyor system as a teenager, pulled green chain, and ended up tending to the log pond. After falling in one day while sorting logs, wet, cold and frustrated he marched in to his dad’s office spouting off his exasperation. W.A. responded with his usual measured but firm manner, “Well now, I figure you won’t learn much about how to run the company by sitting here in the office,” Cart recalled. Then, knowing his father was right, Carlton trudged back to his lowly job.

Part of Woodard’s success came from his risk taking, not blindly but calculated risks. He would carefully investigate the prospect, get expert advice on areas outside his skill sets, then once convinced he went all in.

His predictions usually proved uncannily correct. Gambles on buying timberland during the depression, the increased lumber needs in the east, shipping mixed-length units, and the rise of kiln-dried lumber, all worked successfully in W.A.’s favor.

He partnered with his Michigan associates to establish Bradwood (Bradley/Woodard) near Astoria. Building a self-contained community and mill to harvest the Hemlock that had been left in logged off sections and secured very cheaply. At the time Hemlock was considered to be practically unmarketable but W.A. was convinced the market for its wood would grow, which proved right again!

Diversification was another trait Woodard embraced. He added a plywood plant to his Latham operations, Kimwood, the Woodard mill machinery shop, where many of the plant innovations were launched from became an independent proprietary manufacturer when W.A. sold his mill to Weyerhaeuser in 1957.

Real estate, establishing the Village Green, and charitable work in the community were other ventures Woodard and his sons pursued after the sale of the mill. One anecdote illustrating the ever practical Woodard’s approach to problem solving, involves cow noises and smells.

Soon after opening operations, guests at the Green began to complain about the nearby dairy farm moos and aromas. Woodard bought the land and helped move the herd to a new location, out of nose range. This 125-acre parcel sat vacant until 1990, when after the sale of the Village Green by the Woodard Family, grandsons Kris, Kim, and Casey developed the former farm into the Middlefield Golf Course and Estates, another fruit of their grandfather’s vision.

Described as having a warrior spirit when confronting governmental regulations and other restrictions, but generally pleasant in demeanor, Walter A. Woodard was truly a “Rugged Individualist” who did things the way he saw best through experience, observation, and sheer will, often bucking trends and surviving business climates that would wipe out someone with less fortitude.

The Woodard Building in Cottage Grove is now used to help run the family’s nonprofit foundation. DANA MERRYDAY/PHOTO

The Woodard Building in Cottage Grove is now used to help run the family’s nonprofit foundation. DANA MERRYDAY/PHOTO

We will probably never see either a person of this caliber or the conditions that allowed him to grow from stacking firewood to owning a multi-million dollar lumber company.

Called “The man who built Cottage Grove,” his innovations to the lumber trade and setting up a mill so modern in 1940 that it is still operating today (Weyerhaeuser) despite his releasing the control lever of the log train in December 1957. Then entering into his next phase of shaping our town under the guise of The Woodard Family Foundation, which still continues to contribute thanks to his foresight.

Email: [email protected]