Editor’s note: This is the first of two parts.

As I began to do the research for this week’s Angler’s Log, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration climate summary for July and August became available.

Now we all know it was hot but the summary revealed that at about 74 degrees, July and August 2022 were the warmest July and August in Oregon history. Or at least since 1938 when the “average high temperature” statistics began to be kept.

In what is an “out of the pan and into the fire” scenario, we also had more days that surpassed 90 degrees or higher than ever, too.

Collateral to the rising temperature is the fact that our forests are dry and fires have broken out in several western Oregon locations, including Lane County. The summer fires, seemingly a new normal with choking smoke blanketing our recreation sites, conceal our magnificent vistas, and fill our valleys with fowl air.

With a higher-than-average ambient air temperature, water temperatures in our region have mirrored that increase and are now a couple of degrees warmer than they would normally be, depressing the bite on all of our local cold-water fisheries. In the near term, it limits options for anglers and to every other outdoor enthusiast.

Most concerning is that the warmer, dryer weather is increasingly more common at an alarming rate. A little less so in northwest Oregon but most of the rest of Oregon is in the fifth or sixth year of a persistent and severe drought, the pinnacle of a drying trend that started about 20 years ago.

Is it climate change? I’m not a climate scientist and can only speak to the 45-plus years of sitting in a drift boat on Oregon rivers but I have no doubt that the science is accurate. But indulge me for a bit and let me tell you what I recall about fishing in Oregon about 50 years ago …

In the beginning

We were still Californians, newly married when my wife Tami and I hit the road in our new pop top VW camper van. From our home in San Jose we drove north on Highway 101, spent a night in the redwoods, camping on the banks of the Eel River. Then heading east on the Smith River Highway, we crossed into Oregon east of Gasquet, Calif. We continued through the little towns of Grants Pass and Medford, eventually finding our way to a nearly empty campground in the upper Rogue River Valley.

Like it was yesterday, I recall how clean and green Oregon was. Everything was so lush, creeks flowing with crystal-clear water and the air was the cleanest I had ever breathed. Coincidentally, thousands of half-pounder steelhead had also reached the upper Rogue River. While in college in the early 1970s, I had been half-pounder fishing on the Klamath River a couple of times and had what I thought was pretty good success while using conventional gear. Several years later in ’79, we were pretty green fly anglers and the Rogue was a big and cold river, the biggest river we had ever fished and it was full of half-pounders. More fish than we had ever seen, stacked up on every riffle and in three days of wade fishing we caught and released dozens and dozens of half-pounder steelhead. Far eclipsing any experience I had ever had on the Klamath River and the best fishing Tami and I had ever had as a couple. There were also a lot of salmon that we were not geared up to fish for, but recall watching several people land a couple of the largest salmon I have ever seen.

Bend before the boom

From the Rogue River we drove over the southern Cascades and spent a night at Diamond Lake. We didn’t fish Diamond but learned of its “trophy trout” reputation and planned to return one day. Which we did a couple of years later and, yes, it was as good as everyone had told us. From Diamond Lake we headed north toward Bend. Back then Bend was a dusty little town on the edge of the high desert plateau, a collection of small store fronts, a market and a single fly shop with a gravel parking lot.

It is now a thriving downtown, the fastest-growing city in the state. In a cloud of dust we entered the fly shop and were greeted by a smiling shop owner and a cheerful “Can I help you?” I explained that we were traveling through and were looking for a place to camp and fish. Then with wonderful enthusiasm and an ear-to-ear grin asked if we had ever heard of the Deschutes River? Not being familiar with the Oregon landscape in those days I replied “No.” His look of disbelief was only momentary; he lifted his jaw off the counter, quickly grabbed a map and gave us detailed directions to Trout Creek – a remote BLM camp on the banks of the Deschutes River. And to where a trail continues up the river bank for several miles, offering access to what was then some of the best trout fishing in the world.

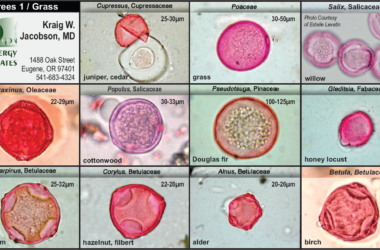

What immediately struck me was the density of bug life on the Deschutes; I had never seen anything as prolific. It was caddis season and the caddis were emerging from the river in clouds. Millions, maybe billions, of caddis and the water was literally boiling with feeding trout. Big, hefty, wild rainbows, the biggest I had ever seen or ever caught up to that time in my angling career. I also came to learn that there were steelhead in the Deschutes and that thousands would return to the river every summer and fall – most noted for their free rising characteristics and willingness to take a swing wet fly.

The Deschutes River, its wild trout and steelhead captivated us and we would return many, many times over the next four decades. I would eventually come to build a guide and outfitting business and 35-year career there. Steelhead fishing was so good in the 1980s and the ’90s that I would often have individual anglers who would catch upwards of 20 steelhead on a fly in three day. As an insult to its former greatness the Deschutes was closed all of last season and part of this season because of warm and poor water quality.

We traded our California driver’s licenses for Oregon licenses in 1980. Upon hearing of our relocation to the Eugene vicinity the owner of the fly shop we had often visited in San Jose proclaimed “You are moving to the bucket” and indeed it was.

Salmon, steelhead and trout, the McKenzie, Willamette and Santiam rivers all just a short drive away. I was a novice but the fishing was wonderful. You still had a good chance to bring home a limit, it was just that good and it was just that good on dozens of Oregon rivers. The climate had not yet become as erratic, it would be another 20 years but another calamity was looming.

The closing of the wild coho fishery in early 1990 was a bitter pill for salmon fishermen. Along the Pacific coast, it brought the fishery to a grinding halt, created boat loads of rules and regulation and is still to this day among the most-managed fisheries in the Pacific Northwest. Poor fisheries management, habitat damage from indiscriminate land use and logging techniques were mostly to blame. Changes to logging practices, to several land-use practices and limits on fishing have also been mandated since then but salmon recovery has been fleeting.

Next week: Current conditions, and how anglers can help.

Email: [email protected]