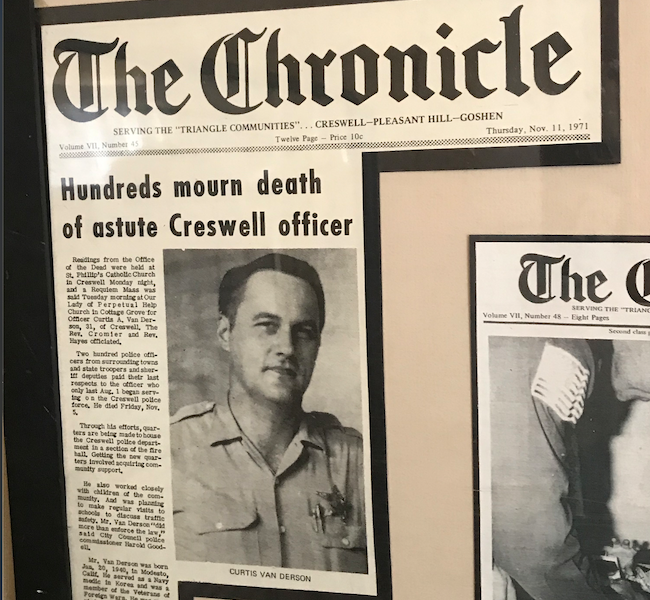

A framed Chronicle edition from Nov. 11, 1971 that hangs in the Creswell Area Historical Museum represents the paper’s longtime commitment to local news.

A framed Chronicle edition from Nov. 11, 1971 that hangs in the Creswell Area Historical Museum represents the paper’s longtime commitment to local news.

I attended a business conference once where the keynote speaker asked the audience for a show of hands “if your team ever makes fun of you and your most-repeated phrases.” Most of the attendees, of course, were unaware or too embarrassed to raise their hands. The speaker made the point that if your team doesn’t playfully imitate you, you’re likely not messaging key points frequently enough.

He was the psychologist for several professional sports franchises, and his point was well taken. (I can also assure you that I had long ago checked off “being made fun of” on my list of career “accomplishments.”)

Back when employees worked in offices, most would waltz past mission statements and “core value” lists without a second glance. The catchphrases and slogans business leaders had hoped would resonate with staff and potential customers were often invisible. The speaker’s central point that day: You can’t take it for granted that people understand your product or mission.

The most prominent branding The Chronicle does is around our hyper-local news coverage. It’s unique and differentiating. It has utility. Overall, it edifies the community.

But what does “hyper-local” coverage actually look like in practice? Consider a few of The Chronicle’s stories in the past few months.

-We met Darren Bollinger, a Creswell resident who owns and operates Bangers & Brews restaurant in Eugene. A great example of how our communities all tie together.

-Business writer Michael Dunne introduced us to Elliot Rohde, CEO of Wise Woman / Earth Lab Botanicals. A global operation, they are the largest private employers in Creswell.

-Jeannie and Floyd Plummer recently purchased the iconic Round Up Saloon in downtown Creswell. We learned why, and how they plan to grow it.

-Longtime Cottage Grove residents and writers Dana Merryday and Don Williams expanded on the losses of local institutions such as the Koffee Kup, Sunshine Market, and The Village Green.

-We learned about W.A. Woodard’s impact on Cottage Grove, which continues to this day through his family and charitable foundation.

–Mona’s Beads in Springfield continues to thrive, despite the pandemic, under the creative energy and sheer will of owner Mona Castle.

-The Chronicle is non-partisan when it comes to politics, and still covers the news of elections. We’ve given extensive space to Creswell’s mayoral candidates — in their own words — as the city seeks to fill an unexpected vacancy.

-We continue to report on twists and turns around Glenwood development.

-We’ve featured nonprofits and the people behind them, such as Julie Weismann and the Hope & Safety Alliance (formerly womenspace), Peggy Whalen and the Family Relief Nursery, and Susan Blachnik with the Creswell Food Pantry, among others.

None of this coverage was “ripped from the wire,” the vast content syndicates utilized by papers that are part of large chains. This includes the Register-Guard, of course, owned by the largest newspaper corporation in the country. We’ve all watched in real time as Gannett’s leaders in Washington, D.C., have dismantled its papers all over the country in order to squeeze every available penny to maximize profits for shareholders.

Not that there’s anything wrong in optimizing profits. It’s a business model.

It’s just not The Chronicle’s model.

I received more than a few sideways glances when I purchased a weekly print newspaper. And to this day people will say, with great empathy, that “You’re in such a tough industry.” “Look what’s happened to print.” “It’s a shame what’s happened to The Guard.”

To be clear, The Chronicle is an entirely different business, operating from a completely different model, than the Register-Guard, or Cottage Grove Sentinel. Or any other newspaper in the country that is owned by a large corporation or hedge fund. The Sentinel might try and make the case that its parent company is “family owned.” Well, so is Wal-Mart.

The Chronicle is owned solely by my wife and I, who live here in the southern Willamette Valley. Our goal is to edify our community, support local businesses, and deliver hyper-local news and information with quality storytelling and photos, all with the utility readers enjoy. We do this in print, and on digital and social platforms, sometimes with audio and video, too.

That hyper-local approach is too expensive for corporations, who use cookie-cutter news-as-commodity content. And it can be done from anywhere and by anyone, they think. The paper is largely produced out of state now. Its deadlines don’t allow for news past mid-afternoon. Forget about coverage of a Ducks night game in the printed edition.

Let me emphasize that this isn’t about the fine journalists and people of character still trying to report, photograph, edit and design the newspapers. There are committed journalists everywhere who still do their best work to serve readers, in spite of soul-crushing working conditions.

The Chronicle, alternatively, delivers stories of your family, friends, and neighbors that aren’t covered or published anywhere else. Written by people who live here.

Writer McKay Coppins published a piece in The Atlantic this past week that took an in-depth look at the secretive Alden Global Capital hedge fund, which has purchased the Chicago Tribune, Orlando Sentinel, and other major daily newspapers.

To be clear: The internet hasn’t killed print newspapers. Greed has.

According to Coppins’ piece, “In the past 15 years, more than a quarter of American newspapers have gone out of business. Those that have survived are smaller, weaker, and more vulnerable to acquisition. Today, half of all daily newspapers in the U.S. are controlled by financial firms, according to an analysis by the Financial Times, and the number is almost certain to grow.

“What threatens local newspapers now is not just digital disruption or abstract market forces. They’re being targeted by investors who have figured out how to get rich by strip-mining local-news outfits. The model is simple: Gut the staff, sell the real estate, jack up subscription prices, and wring as much cash as possible out of the enterprise until eventually enough readers cancel their subscriptions that the paper folds, or is reduced to a desiccated husk of its former self.”

Sound familiar?

The Chronicle publishes obituaries for free. I’ll repeat that at the risk of being mocked. We publish obituaries and photos on a Tributes page for free. We give reduced advertising rates to nonprofits. We are entirely unlike The R-G and The Sentinel in the local market. And just about every other paper in the country.

So what? Coppins writes: “This investment strategy does not come without social consequences. When a local newspaper vanishes, research shows, it tends to correspond with lower voter turnout, increased polarization, and a general erosion of civic engagement. Misinformation proliferates. City budgets balloon, along with corruption and dysfunction.”

Simply put, our business model is designed to serve and uplift our communities — both readers and local businesses. It’s not to squeeze every penny out of them while degrading both newspapers and the communities they serve.

Noel Nash is publisher of The Chronicle.