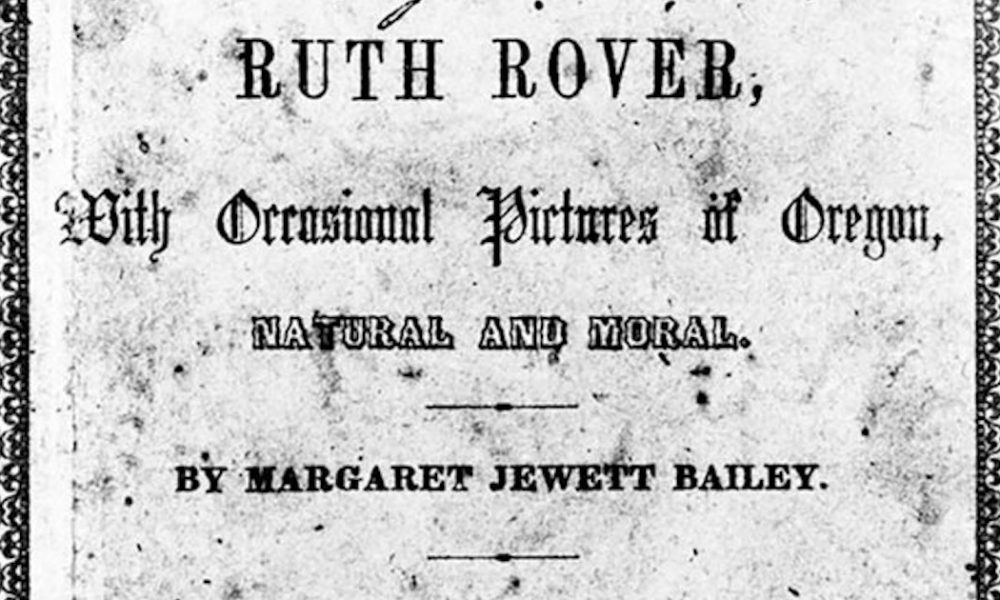

The title page from the original 1854 edition of Part Two of the first novel-length work of (alleged) fiction ever published in Oregon, by Margaret Jewett Bailey. IMAGE: oregonencyclopedia.org

The title page from the original 1854 edition of Part Two of the first novel-length work of (alleged) fiction ever published in Oregon, by Margaret Jewett Bailey. IMAGE: oregonencyclopedia.org

Early in the summer of 1854, an advertisement appeared in the Portland Oregonian – a tantalizingly feisty one, from an author braced for combat and essentially inviting the world to ”bring it on”:

”A new work will be published, about the 1st of August, the first number of ‘The Grains; or, Passages in the Life of Ruth Rover’ … by Margaret Jewett Bailey,” it began; then launched into a ferocious little stanza of unrhymed mixed-format verse:

”Thou Monster Evil – stand forth!/ And in whatever garb thou mayst appear,/ Whether harlot, villain, priest or Pope,/ I challenge thee to single combat.”

The ad finished with some business details: the book would be published in ”monthly numbers” until it was completed; and to order a copy, one was invited to write to Jewett in care of the publishers of the Portland Times newspaper, with which she had contracted to publish it.

This ad likely generated quite a bit of buzz, with its coy references to harlots and popes; but it’s also likely that it would have generated plenty of attention even without them. The news that Margaret Jewett Bailey was about to publish a tell-all has to have gone through the tiny Oregon frontier community like an electric current. Bailey was, by the time she wrote her book, a little notorious.

She had been one of the first white women to come to the territory, back in the 1830s, when she joined Jason Lee’s Methodist mission near Salem, and her voluble personality caused all kinds of drama and trouble there – culminating with her fiance’s attempt to pressure her into going through with their planned marriage by ”confessing” to having had premarital sex with her. Professionally ruined by this, she’d left the mission and married a wealthy and prominent (but unpleasant and alcoholic) physician. Then she’d become Oregon’s first female journalist, publishing a poem in the very first issue of The Spectator, Oregon’s very first non-handwritten newspaper, and running the women’s page for a couple months before feuding with the editor and quitting in disgust.

She had a record of uninhibited and acerbic writing; she was preparing what appeared to be a super-racy tell-all memoir; and she had just secured a divorce from a prominent community member about whom they’d all heard some pretty tantalizing rumors. What was not to like?

Well, plenty, if you ask any of the various journalists who reviewed the first installment.

C.L. Goodrich, the editor of the Spectator, was already embroiled in a hot feud with his former columnist, and seems to have been a little bitter about her decision to have her book printed at the Times instead of the Spectator. Upon her departure, he wrote, ”We promise to allude no more to the lady who asked us how much we would take to print ‘her life and sufferings,’ after we had positively told her nine different times that we didn’t want the job at any price.”

That kind of petulance has to have raised a few eyebrows among readers, especially after the job was happily taken up by Goodrich’s competitors at the Times, and that may be why his review of the book was short and relatively noncommittal, merely mentioning that his opinion of its low quality had not changed.

In the Oregonian, though, a pseudonymous reviewer calling himself ”Squills” went after it with astonishing savagery. After expressing his belief that women should stick to ”darning stockings, pap and gruel, children, cookstoves, and the sundry little affairs that make life comparatively comfortable,” he added, ”Afflictions will come upon us, even here in Oregon; where we are castigated with so many already. It is bad enough to have unjust laws – poor lawyers and worse judges – taxes, and no money … without this last visitation of Providence – ‘an authoress.’”

Then, following several paragraphs that drip with sarcasm and vitriol, he finishes with this little nugget:

”To call it trash would be impolite, for the writer is an ‘authoress.’ … When a Napoleon, a Byron, or any other lion makes his exit, it is well enough to know ‘How that animal eats, how he snores, how he drinks.’ But who the dickens cares about the existence of a fly, or in whose pan of molasses the insect disappeared.”

Copies of the first installment must have sold well – which is not surprising, with that kind of press out there. Surely everyone had to at least glance at a copy and see what the fuss was about. And at $1.50 a copy, it was far from cheap; so most likely Margaret made a profit on the first part.

She may not have done as well on the second, though. By the time it came out, everyone had seen what all the fuss was about; and the first part of the book builds fairly slowly, with dozens of pages recounting the life of a virtuous young woman with a passion for Jesus defying her father to join a faraway mission and journeying to Oregon via Hawaii, before getting to the juicy parts. At the end of it, ”Ruth Rover” meets ”Dr. Binney” (in real life, Bailey) on March 3; marries him on March 4; and leaves the mission that very day.

”In our next number we will continue our narrative of Ruth Rover, and endeavor to show how fully she drank the ‘cup of sorrow to the dregs’!” it finishes.

With Part 2, she included a witty and cutting personal note to ”Squills” in the epilogue that really showcased her skills as a writer, which were noticeably superior to those shown in ”Squills”’s column. ”Squills,” in his response, resorted to claiming that the second installment was too smutty to review or quote from, and instead actually quoted a passage from the Oregon Territory’s obscenity law. This cannot possibly have had a negative impact on sales. One almost grows suspicious that the two of them were in cahoots.

If they were, though, it apparently wasn’t effective enough. The second installment of Grains was destined to be the last. It’s also less interesting than the first installment, being basically the complete story of a very unfortunate 15-year marriage, from ”I do” to ”You’re fired”; and it was pitched openly as a sob story, rather than a titillating tell-all. Most people don’t want to read sob stories.

Whether for that reason or others, no more of ”Ruth Rover” was ever published.

The book’s halflife in the marketplace was very short. People read it with avidity and then threw it away like yesterday’s newspaper. For many years it was thought that no copies had survived, and people who disapproved of Margaret claimed that was because the book was an obscene and badly written failure, and the few copies that did sell had all been destroyed by outraged readers. This is patent nonsense.

”It was the true-confessional tale of its day, laying bare a scandal involving well-known figures, and so interesting reading that the slender 96-page books could be sold for $1.50 each,” historian Herbert Nelson writes in his 1944 article. ($1.50 in 1854 was worth the equivalent of almost $50 today – rather a lot for half a novel.)

But ”Ruth Rover” was essentially the 1850s equivalent of an airport novelette, and nobody was going to bother saving a copy of it, especially in an age when old Sears catalogs and other unimportant books and papers were being regularly repurposed as toilet paper.

Fortunately, a copy of the second installment was discovered in 1935, and a mostly complete copy of the first surfaced several decades after that. In 1986, the Oregon State University Press undertook to consolidate and republish the whole thing, in what can only be described as a generous act of historical curation; it’s inconceivable that this turgid-but-important historical book will ever sell enough copies to be profitable. But, as a result, the first novel-length work of alleged fiction can now be read and studied.

As for its author, for the rest of Margaret Jewett Bailey’s life, through several marriage-induced changes of surname, she was constantly being referred to as ”Ruth Rover.” The claim that her book was about someone else was never bought for an instant.

She continued to be something of a stormy petrel; drama always seemed to seek her out. She married again, to another horrible man, whom she divorced after claiming to have discovered that he had impregnated his own daughter while married to her. The argument over whether he did or not ended up playing out in back-and-forth paid advertisements in newspapers.

She married a third time, to a man named Crane, after moving to Washington; and maybe this marriage took – we know nothing about him, which for a husband of Margaret Bailey is a very good sign. She died in May of 1882; and the first line in her obituary in the Puget Sound Weekly Courier read, ”Mrs. Margaret J. Crane, author of ‘Ruth Rover,’ a novel that created a great sensation in Oregon in early days, died in Seattle Tuesday night of pneumonia.”

Not bad for a ”fly,” about whose existence ”who the dickens cares.” One wonders if ”Squills,” whoever he was, ever did half so well.

(Sources: ”First True Confession Story Pictures Oregon ‘Moral’” (sic), an article by Herbert R. Nelson published in the June 1944 issue of Oregon Historical Quarterly; ”The Grains; or, Passages in the Life of Ruth Rover…”, a book by Margaret Jewett Bailey, in an edition edited by Evelyn Leasher and Robert J. Frank, published in 1986 by OSU Press)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. His book, Heroes and Rascals of Old Oregon, was recently published by Ouragan House Publishers. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.