Whiteman Community Park in the Northwest Neighborhood a result of the 1980-1983 HUD Block Grant.

Whiteman Community Park in the Northwest Neighborhood a result of the 1980-1983 HUD Block Grant.

Last week we traced a few of the reasons that citizens of Cottage Grove so passionately viewed Mt. David as public space. Generations of Grovers had used this hill as their collective backyard. When it snowed, every kid in town who had a sled would be riding down its slopes. Those not so blessed would use a piece of cardboard or even just their breeches. Often the sledding was accompanied by a festive bonfire on the summit.

Fire was a common occurrence on Mt. David. Mostly a grass pastureland, it was common for fires to start with a little help from kids with matches or other careless acts. It was understood that it was a community effort to put out the blazes, so everybody pitched in for the common good.

This idyllic arrangement was to come to an end in the 1970s when a large portion of Mt. David was sold to Forrest Solomon of Mazama Timber Products in Creswell. In 1977 residents were shocked to learn of plans to put apartments, houses, duplexes, and townhouses, on the lower slopes of the historic hill.

The land at that time was not included in the city limits and under the jurisdiction of Lane County. The county zoning allowed for up to 500 units on this parcel. To receive city water and sewer services the area would need to be annexed into the city limits. In order for this to happen the first step would be petitioning the Lane County Boundary Commission.

The prospect of turning the grass and woodlands that had been used recreationally for years into housing concerned many because of the steep slopes and the fear of runoff and slides, in addition to the feeling of loss of this natural paradise to progress.

A group formed out of the neighborhood most affected, (Ash, Birch, and Chestnut streets), calling itself “The Northwest Neighborhood Council.” They worked together to express their concerns and to attempt to try and preserve the natural areas as much as possible.

An account from Dec. 14, 1977 in the Cottage Grove Sentinel describes the reception of a petition presented by the NW Neighborhood Council to the City Planning Commission. The group stated with its request that the city “Recognize Mt. David as a unique area and to hereby ask for the moratorium for the preservation of its natural beauty.”

Preston Smith, a planning commissioner, met the request with a mild rebuff. Since there were vacancies on the City’s comprehensive planning advisory committee, he suggested while he was pleased to see the petition he had these words for the signers: “If you don’t show up at those meetings and help us formulate that policy, you should be ashamed to have your name on that petition.”

This sentiment reveals some of the tensions that were in the community. While many wanted no change to come to the hill, others saw development as progress and opportunity.

Ultimately these initial plans at development failed because of economic realities and due to the uproar that had come from the community. If Mt. David was to be developed there would need to be lots of questions answered and problems solved.

The next phase of the Mt. David story came in October 1979, when the City invited the Northwest Neighborhood (NWN) members to a series of public meetings to consider applying for a federal Housing and Urban Development grant. The aim of the grant was twofold: Since the NWN was the oldest in the city, its infrastructure was in need of a serious rehab. Secondly, if Mt. David was to be developed, access to the hill lay through the NWN so residents and the city both naturally wanted to insure that development didn’t negatively affect the neighborhood.

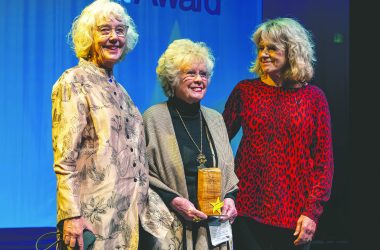

A $1.4 million community development block grant was awarded by HUD and a three-year process was begun to improve life in the NWN. A steering committee was formed of eight community members, chaired by Becky Venice. There was at times tension and mistrust between city and NWN members as the process worked through the many intricacies required by the grant and identifying the priorities of the NWN. Some residents were suspicious that the block grant was an underhanded way to open up Mt. David to development.

What did come out of the process were significant improvements to the NWN and a pretty unified neighborhood. The residents met many times to work out what their priorities were, and socially as well. A consultant was hired to help the group implement the overall plans and find alternatives when problems arose.

There was a newsletter to keep residents informed of meetings and progress, pie parties, yard concerts, and garage-sale fundraisers. Lasting legacies of this process can still be experienced in the NWN. Streets were resurfaced, sidewalks fixed or replaced, one new city park was added and one improved (Whiteman Community Park & Westend Park), street trees added, and money was made available for residents to paint and otherwise spruce up the appearance of their houses. Less visible but vitally important was the replacement and upgrades to the sewers and water lines in the NWN. The alleyways that had been neglected or taken over by fences, parked cars, and trash were cleared and returned to public use.

The results were proudly shown off in 1983 as the finishing touches were added and the NWN invited everyone to tour the rehabilitated neighborhood.

Some other events that played a big role in changing the fate of Mt. David occurred in the 1980s. One was the sale of the Mazama Timber holdings of land to the California developer Fred Brown. Another was in 1987, when a fire that pretty much burned everything on the eastern side of the hill. Karen Larson, a popular high school biology teacher, led her students and others in planting some 1,200 trees to replace those lost to fire. Many of them are still standing.

Other Mt. David trees that ignited public outrage fell to bulldozers in August 1990. Residents were shocked and enraged when trees that had stood like sentinels over the town for more than 100 years bit the dust to make way for Brown’s plans to build 200 homes on the butte over a 10-year period.

The clearing had occurred primarily on the north side of Mt. David but residents along the Hidden Valley Golf Course, River Road and in the NWN, were concerned about possible run off and mudslides from the vast areas of land exposed just before the start of the rainy season.

Since the land lay outside of the city limits there was little City officials could offer to citizens who went to protest the action. Through another quirk in county regulations, owing to the fact that the tract did lie in the Cottage Grove urban growth boundary, Lane County also had no say in the matter. As long as Brown had notified the Department of Revenue, there was no way of stopping a private landowner from doing what he wishes with his property.

Another issue that came out at this time was the possibility that Kalapuya burial and cultural sites were being destroyed by the bulldozing. Again, a private developer operating on private land negated state and federal antiquity laws from applying to this case.

Brown did stop clearing, and the recession of the early ‘90s had the last word on his plans to build some high-end homes on the hill. The land sat partially denuded and idle until 1996 when Brown asked Lane County to transfer planning authority to Cottage Grove and announced plans to install sewers, utilities, and streets. But suddenly the land was being put up for auction with an asking price of $695,000.

When no takers snapped up the land, it gave birth to a new group and efforts to try and preserve Mt. David as public land. The residents called themselves “The Friends of Mt. David.” NWN resident Karen Kempf founded the group and served as its president. Don Nordin served as the vice president and it organically grew to include about 50 sustaining members and as many 200 others involved at various levels.

The group helped on a deal that led to a portion of the land being broken off the main parcel and sold to local developer Ron Scroggin. His plans included the rock outcrops considered sacred to the Kalapuya and other probable heritage sites.

Kalapuya storyteller and cultural consultant Esther Stutzman joined the FOMD, wanting to preserve as much of Mt. David’s cultural and natural history as possible. Stutzman and FOMD eventually agreed to withdraw their appeal to block the development after Scoggin agreed to allow an archaeological survey of the area and to withhold development of the three lots that surround the sacred rock outcrops. The current View Heights Subdivision/Kalapuya Way is the result of this compromise.

Read part 3 here.

Email: [email protected]