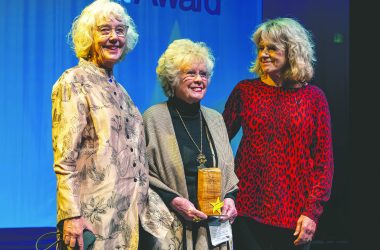

DANA MERRYDAY/PHOTO

DANA MERRYDAY/PHOTO

Cottage Grove’s wastewater plant was first built in 1953 to handle 6,000 residents.

Part I of a two-part series.

COTTAGE GROVE – Most folks don’t want to think about what happens when they flush the toilet. They are happy enough to see that swirling vortex, to hear the reassuring sound of a flush, thinking that it is now somebody else’s problem. But when a toilet gets clogged – or worse, there is a blockage between the seat and the street – that’s when we realize that “somebody’s else’s problem” really belongs to us.

Every flush, unplugged tub, washing machine rinse cycle – any of the ways we take clean water and make it dirty – becomes the job for Cottage Grove’s wastewater treatment facilities staff. It’s their responsibility to turn that soiled water back to a clean, safe, vital-for-life liquid.

Water is essential for life. Under ideal conditions, you can survive maybe seven days without water. Most settlements were chosen with water in mind. Cottage Grove grew up on the banks of the Coast Fork Willamette River when Harvey Hazleton set up his mill in 1857 where Silk Creek runs into the river.

The river provided power and was a water source for irrigation, animals, and further downstream transportation. Human waste was disposed of in privies and cesspools, and later, in the river. As long as the population was small, moving water purified itself through oxidation and absorption by the lush vegetation along the banks. When the population grew, dumping waste into the river was no longer a viable option.

From the Native peoples on up, the majority of Oregon’s population has lived in the Willamette basin. With so many people using the rivers and dumping everything imaginable into them, it wasn’t long before water quality deteriorated and the health of the river – including the aquatic and human life that depended on it – began to decline, according to “A History of Water Pollution Control in the Willamette Basin, Oregon,” by the U.S Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

“Early riparian users proclaimed a right to remove from and put into the river whatever was to their individual best interests,” according to the report. By 1926, it was clear to enough basin dwellers that this philosophy could not continue. Erosion, pesticides, industrial wastes, and raw sewage had affected aquatic life, so much so that a 10-mile stretch of the Portland Harbor is still labeled a “superfund toxic waste” site.

The Oregon State Board of Health made the first move when it called a group together in Salem to identify the scope of the problem, and formed the “Anti-Stream Pollution League.” A newly assembled committee studied river conditions, and met with the League of Oregon Cities to hammer out legislative action.

Other groups joined, including the Portland City Club. Over 60 cities provided records of water quality and sewage, which were added to bacteriological reports and State Health Department findings. In 1929, a preliminary report prepared by the OSU Engineering Experiment Station identified key issues and called for a sanitary survey of the Willamette.

In July 1929, research teams measured water flow, temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO) content and bacterial counts from 28 sampling sites along 200 miles of river, starting at Cottage Grove. Results indicated that, by the time the water reached Portland, it was so depleted of DO that it was nearly impossible for fish to survive.

In the early 1940s, this finding was dramatically presented to the public. It was presented in a silent documentary film, showing young fish being placed into the river in a wire basket, gasping for air and eventually dying. This report moved then-Gov. Julius L. Meier in 1933 to call for a Mayor’s Conference for the cities of the Willamette to respond to the public sentiment that it was time to clean up the river.

When regulations are proposed, the economic impact is always a point of contention. Four large paper and pulp mills along the river were identified as major sources of contaminants. Raw sewage was also a substantial concern, because in addition to affecting water quality, there was the disease component connected with human bio-wastes.

A successful voter initiative led by a coalition of anti-pollution and sport fishermen mandated the formation of the Oregon Sanitary Authority (OSA), a regulatory agency, in 1939. The agency put industry and municipalities on notice that the days of dumping into the river were over. But foot-dragging and World War II effectively stalled the reform efforts.

In another river study in 1944, the OSA found that the river had considerably deteriorated since the 1929 study, and that sludge rafts floated on biologically-dead sections of the river. With the war winding down, the OSA stepped up its efforts to extract action from the offending parties, and Willamette residents voted “yes” for the money to build new wastewater treatment facilities. The first plant was built in Junction City in 1949. Cottage Grove followed in ’53 with a plant designed to handle 6,000 residents.

To have a healthy river for fish and human life it is essential to have the following conditions: enough flow in low-water times (summer), cool water temps, and that the nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon added to water by human use is removed.Nitrogen and phosphorus are nutrients for plant life and bacteria. If they are dumped into the river, the biological oxygen demand consumes whatever DO is around and could lead to algae blooms.

My research didn’t turn up what Cottage Grove did with its sewage prior to 1953. I imagine the town was largely dependent on septic tanks to handle sanitation. In “Golden was the Past” it mentions long-time city engineer Les Coiner had been designing a sewer for years. When he retired in 1966, the task was handed off to Roger Sinclair, the new engineer who upgraded the ’53 sewage plant. A bond had been approved in ’66 to build a tertiary (third stage) sewage treatment, then only the second of its kind in the USA. At the ’68 dedication of the facility, Gov. Tom McCall drank some of the treated water. McCall was an advocate for cleaning the Willamette and he made the cause a central part of his administration. His documentary on the Willamette River, “Pollution in Paradise,” made while he was a TV commentator, was instrumental in getting the public behind his policies.

Cottage Grove’s new wastewater treatment plant was listed as one of the accomplishments on the application to be an “All American City” in 1968. When Cottage Grove was selected as one of the 22 finalists, a delegation from the city flew to New Orleans to lobby for their selection. City attorney Herb Lombard Jr. borrowed McCall’s move and informed the panel that, what he was drinking during his talk was treated effluent from the sewage plant, which had a “dramatic effect” on the jurors.

Whether it tipped the scales is not known, but after the announcement of Cottage Grove’s selection, Look magazine featured our town and made a big deal of the water treatment plant.

Email: