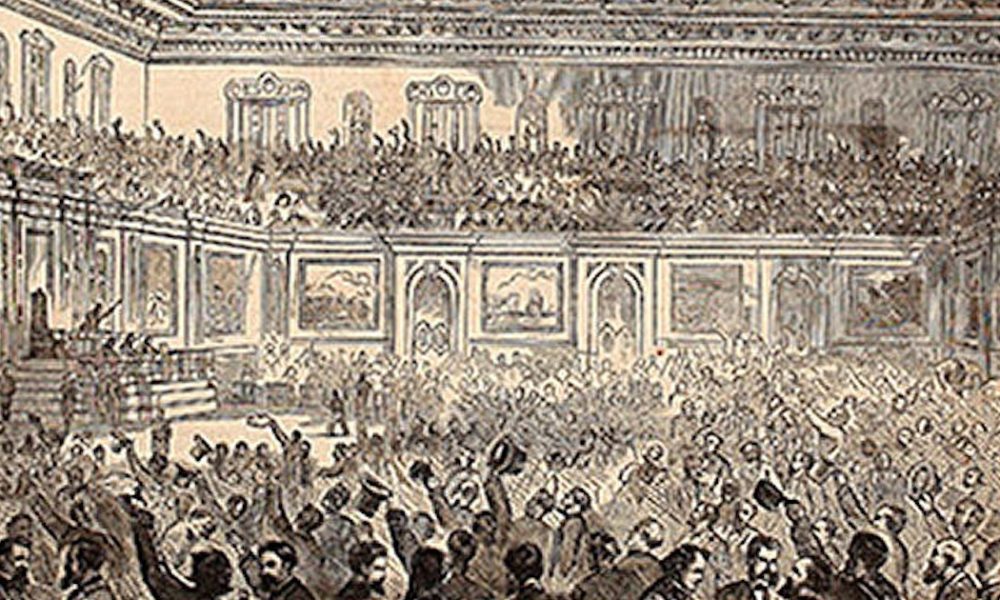

This illustration from the Feb. 18, 1865 issue of Harper’s Weekly shows celebration breaking out in the U.S. House of Representatives after the 13th Amendment was passed. Image: Archive ORG

This illustration from the Feb. 18, 1865 issue of Harper’s Weekly shows celebration breaking out in the U.S. House of Representatives after the 13th Amendment was passed. Image: Archive ORG

The urban-rural divide in Oregon is something that’s gotten quite a bit of press recently, after a group of Republicans left the state to deny a quorum for a bill they opposed.

But it’s a problem that’s been around, in Oregon, since well before the place even became a state. And it probably hit its high-water mark in 1868, just three years after the Civil War – when an insurgent majority from the rural party actually voted to renounce the 14th Amendment to the Constitution – the one that guarantees equal protection under the law to all citizens, and establishes automatic birthright citizenship.

In its earliest beginnings as a U.S. territory, Oregon was more or less divided into two broad categories of people: homesteaders from Missouri and surrounding states who arrived on the Oregon Trail, who tended to settle in the rural areas; and Yankee traders and businesspeople from New England who arrived by ship, who established themselves in the principal cities.

On the great question of the 1840s and 1850s – slavery – the rural and urban Oregonians were essentially in agreement. The Yankee traders, of course, found slavery morally repugnant, not to mention unnecessary. And the homesteaders, although they came from slaveholding states, were adamant about keeping the institution of slavery out of the new state, not for moral reasons but for economic ones – they saw it as unfair competition.

But the white pioneers, on both sides, were still very much products of their time – that is, un-self-consciously racist. And they didn’t want free blacks competing with them for land and resources.

This, of course, is why the territorial Legislature approved the infamous ”lash law,” by which black people, whether slave or free, had to report every six months for a beating until they took the hint and left the state. The lash law was never enforced, but it was on the books in 1844 and was followed by other, less egregious laws calculated to make it very clear that the opportunities of the new Oregon lands were for whites only. And it’s also why Oregon was the only state to have entered the union with a racial exclusion clause in its actual constitution – which, although not enforced, stayed on the books until the 1920s.

That’s not to say the urban and rural parties agreed about everything. Politically, the Yankees were Republicans and the Southerners were Democrats. That, obviously, became a pretty hot issue in the runup to the Civil War.

Then, after the war, a torrent of what amounted to refugees started flooding into the state from the defeated South. Lots of Southerners who had gone into the war as respected members of their communities finished it as penniless tramps. Plenty of them, looking around their ruined and smoking communities, decided they had nothing to lose; so they headed west, looking for new opportunities.

Oregon’s population boomed in the years after the war; and nearly all the newcomers were ex-Southerners. The vast majority of them wouldn’t have voted for the party of Lincoln if their lives were at stake.

So with startling speed, the balance of power shifted in Salem.

It had already started to shift in 1866, when the 14th Amendment came up for a ratification vote in the Legislature. The vote, held on Sept. 19, was 25 to 22 for ratification; but three days later, Grant County’s two Republican state legislators were found to have actually lost the election. They were removed; their Democratic opponents were seated; and the two newcomers were not slow in pointing out that they would have voted against ratification if they’d been properly seated.

There followed some partisan wrangling as the disappointed Democrats tried to pass a resolution taking Oregon’s consent back. The Republican majority hastily circled its wagons, called in its wandering voters, and defeated it. The ratification would stand.

But the Republican majorities in the House and Senate – they would not stand, at least not for much longer. As more and more committed Democrats poured into Oregon from the ravaged lands of the Confederacy, and more and more locals soured on Reconstruction, the once-dominant Republicans found themselves suddenly on the outside looking in. And 1868 made it official: Dems outnumbered Repubs 13 to nine in the senate, a 59 percent majority; and 30 to 17, a 64 percent edge, in the House.

(As a side note, these figures are almost uncannily similar to the ”supermajority” ratios today. As of 2019 the numbers today are 18 to 12 in the Senate, and 38 to 22 in the House. That’s 60 and 63 percent, respectively.)

Upon arriving in the capitol in full control of the works, the new Democratic majority announced three main goals: 1) to force the state’s U.S. Senators, Republicans Henry Corbett and George Williams, to resign so that they could be replaced with Democrats; 2) to redistrict the state in such a way as to, as historian Frances Fuller Victor put it, ”increase the Democratic representation in certain sections and decrease the Republican representation in others”; and 3) to rescind the state’s ratification of the 14th Amendment.

It was an ambitious agenda. Corbett and Williams, of course, declined to comply with the demand for resignations – although in 1870 Williams came up for re-appointment and could be, and was, replaced then.

One assumes the gerrymandering went according to plan, as it usually does; but it couldn’t have offered them too much protection, since the Republicans were back in power again four years later.

But the rescission of the state’s approval of the 14th Amendment: that was the big one. The Democrats were basing their move on the claim that the amendment had never been legitimately ratified. The defeated Southern states had all voted for it; but doing so had been a condition of readmission to the union. The Democrats felt that this was like enforcing a contract that had been signed at gunpoint. As far as they were concerned, the amendment had not yet been legitimately ratified, and until it was, anyone who wished to do so could withdraw their consent.

So, just a day or two into the session, Sen. Victor Trevitt of Wasco County proposed the bill.

”The legislatures … of the states of Arkansas, Florida, North Carolina, Louisiana, South Carolina, Alabama and Georgia [were] usurpations, unconstitutional, revolutionary and void,” the bill asserts – referring, of course, to the ”carpetbagger” legislatures in those states just after the war. ”Until such ratification is completed, any state has a right to withdraw its assent to any proposed amendment.”

The redoubtable Republican Harvey Scott, editor of the Portland Oregonian, was neither slow nor subtle in his response to all this.

”In making a raid on the Fourteenth Amendment, Sen. Tappertit Trevitt’s evident object is to strike a blow at ‘[slur deleted] equality,’” he wrote on Sept. 24.

In the same article, Scott also claimed that Trevitt had obtained his seat through ”fraud and rascality.” (This may have been a reference to Trevitt’s having many years before reneged on a ”gentlemen’s agreement” with his opponent in which each had promised to vote for the other. Trevitt’s opponent did so, but Trevitt, when he saw how close the tally was, voted for himself, and in the end won his seat by two votes.)

On Sept. 28, Scott wrote a sarcastic article urging the Democrats to go ahead and abrogate the United States Constitution. ”Let them come out squarely for nullification,” he wrote. ”Elected by the votes of Democrats from the Southern army, it is fit that they should perpetrate this act of rebellion.”

Beriah Brown, editor of the staunchly Democratic Portland Herald, responded the very next day with what has to be one of the most ironic statements ever to appear on a newspaper editorial page. He acknowledged that the vote wouldn’t likely change anything; but, he added, it would put Oregon on the right side of history, ”as favoring a white man’s government.”

Though in a tiny minority, the Republicans managed to delay the vote on this box of dynamite for a week or so. But finally, on Oct. 6, it passed on a straight party-line vote.

Scott was ready for them, and unleashed a five-deck headline on the second page:

”THE ACT CONSUMMATED! / Passage of the Secession Ordinance by the Oregon Senate! / The Democratic Party Repudiate the Constitution! / OREGON OUT OF THE UNION!”

The act directed that Oregon’s rescission be forwarded to the President and Secretary of State, and presumably this was done, although historian Johannsen was unable to find any documentation of it. Harvey Scott suggested that President Grant would ”probably use it to light a cigar, while the copy sent to Congress (would) either go under the table or on file as a curiosity in the room kept for the rebel archives.”

In the end, Herald editor Beriah Brown was right. The passage of Oregon’s rescission act had no effect at all, other than to sully Oregon’s reputation.

(Sources: ”The Oregon Legislature of 1868 and the 14th Amendment,” an article by Robert W. Johannsen published in the March 1950 issue of Oregon Historical Quarterly; History of Oregon, Vol. 2, a book by Hubert Howe Bancroft (pseudonym for Frances Fuller Victor) published in 1888 by The History Company; To the Promised Land, a book by Tom Marsh published in 2012 by OSU Press)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. His book, ”Heroes and Rascals of Old Oregon,” was recently published by Ouragan House Publishers. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.