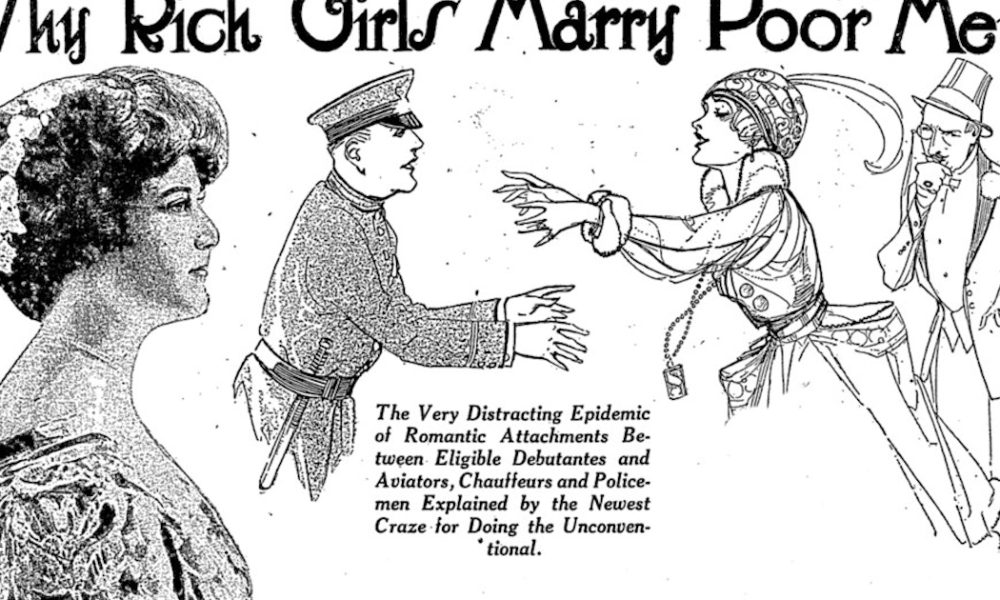

This photo spread ran in the Society section of the Portland Morning Oregonian on Nov. 29, 1921, shortly after Oregon’s ”Diamond Bill” Barrett scandalized New York society by eloping with its most eligible debutante, Alice Drexel – whose profile is shown at the left side of this montage. Image provided/UO Libraries

This photo spread ran in the Society section of the Portland Morning Oregonian on Nov. 29, 1921, shortly after Oregon’s ”Diamond Bill” Barrett scandalized New York society by eloping with its most eligible debutante, Alice Drexel – whose profile is shown at the left side of this montage. Image provided/UO Libraries

Every now and then, one runs across a man who can sweet-talk absolutely anyone into anything.

Such a man was William ”Diamond Bill” Barrett Jr., the black sheep of a solid, respectable family of Hillsboro pioneers.

As a character, Diamond Bill was like a 20th century version of George Wickham, the rakish Army officer in Jane Austen’s novel, ”Pride and Prejudice.” Like Mr. Wickham, Diamond Bill was a dashing, handsome military man with a particular talent for persuading the daughters of wealthy families to elope with him.

Call him, if you will, ”The Heiress Whisperer.”

As a teenager growing up in Washington County in the first decade of the 1900s, Diamond Bill seems to have been a real handful for his father, State Senator William Barrett Sr.

He was, in the vernacular of the day, a ”fast young man” – a high roller and a big spender with a habit of running up hefty gambling debts that he lacked the wherewithal to pay; and, in the interest of avoiding scandal, his father would scurry around after him squaring his accounts afterward.

Perhaps hoping that a military education would straighten him out, William Sr. sent the young rake off to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, and he did well there, graduating and taking a post as a midshipman. But very shortly thereafter, he and the Navy parted ways – most likely as a result of a 1911 incident in San Francisco that clearly didn’t rise to the Navy’s famous ”officer and a gentleman” standard. This was the incident that earned him the moniker ”Diamond Bill:”

Ashore in San Francisco, Bill visited a jewelry store and, pretending to be a wealthy swell and turning on that legendary Diamond Bill charm, actually talked the proprietor into letting him borrow a $2,000 diamond ring (worth about $55,000 in 2019 money) to take home and ”see if my wife likes it.”

He then headed for a pawnshop, hocked the ring for $1,500, returned to the jewelry store, and arranged to pay for the diamond over four months with $500 monthly payments. He then made his first month’s payment, and left with $1,000 in clear cash money.

He then started to work the same play on a second jewelry store, but by the time he did, the police had noticed the unusually large $1,500 pawnshop payment. Diamond Bill was collared by a bluecoat and parked in the city joint on suspicion of being a diamond thief.

The cops assumed it was his intention to run, leaving the jeweler holding the bag for the $1,500 balance owed on the hocked ring; but it’s far more likely that the target of Bill’s swindle was his father, who he must have expected to make good on his debt as he always did. Otherwise, he wouldn’t have used his real name.

The judge threw the case out of court, observing acidly that no crime had been committed: Bill had bought the diamonds on credit, but he wasn’t behind on payments and he was perfectly within his rights to pawn his property if he wished.

Senator Barrett hastily covered the debts, and the matter was forgotten, except that from that day forward, the young Mr. Barrett was saddled with the flashy nickname ”Diamond Bill.”

Diamond Bill’s next big score came three years later, in 1914, when he wrangled an introduction to Miss Kathleen Baillie of Tacoma, the daughter of one of the richest men in Washington State. Following a whirlwind romance, the couple eloped, married and moved to New York.

It’s not clear what happened with Diamond Bill’s marriage to Kathleen, but something obviously did, because in roughly one year it was over, and Kathleen was suing for divorce.

Shortly thereafter, the Great War broke out, and Diamond Bill, instinctively identifying the Army Air Corps as the most dashing and romantic arm of the service, wrangled his way into it. He served in France with sufficient distinction to be promoted to the rank of captain, and at the war’s end he was proudly calling himself Captain Bill – not quite as colorful as Diamond Bill, but decidedly more respectable.

It was as Captain Bill Barrett that he then, in 1919, managed to work his way into the good graces of Miss Alice Drexel – heiress to the John Drexel fortune, one of the biggest in New York.

In keeping with our ”Pride and Prejudice” analogy, Alice apparently had as much in common with Lydia Bennett as Captain Bill did with Mr. Wickham. She seems to have been a bit boy-crazy, and had four ardent suitors, of whom Captain Bill was one; and her mother, fearful that things would get too serious, was hastily arranging for a family trip to Europe. Before that could happen, Captain Bill convinced Alice to elope with him. They slipped away by night in an automobile to New Rochelle, got married in a little church, checked into a posh hotel on Fifth Avenue – and then Alice called her mother.

The conversation did not go well.

The young couple was summoned to the family manse to continue the discussion; there, the conversation went even worse. The upshot was that the newlyweds headed off across the ocean for a tour of Europe without any financial support from the Drexels … and Diamond Bill found himself having to try to maintain an heiress in the condition to which she was accustomed, on an Air Force captain’s salary.

They bounced around a bit in three-star hotels and railroad apartments, and one imagines Alice getting more and more disillusioned with the whole affair.

Then finally, one day, Diamond Bill just bounced. He vanished from their room, leaving her flat broke and pregnant to boot, and hustled home to America.

It would be a while before Alice learned why he left when he did. It had to do with her friend, Sydia ”Sidi” Wirt Sprinkels, dashing show-girl wife of a San Francisco sugar magnate’s son. Bill had run into Sidi in London, to which city he’d traveled for some business reason, leaving his new wife in their shabby digs in France; he and Sidi were already acquaintances from the old days when he’d been a man-about-town in San Francisco and she’d been a Vaudeville star there.

Sidi was in London by herself; she and her new husband had apparently quarreled on their honeymoon, and he’d ditched her and run off to Norway; she was left wondering if he planned to return, and if not, how much money she could get out of the $120,000 string of pearls that he had given her as a wedding prezzie.

”Alone as you are, in this big city, I should think you would be afraid to wear those beautiful pearls in public,” Diamond Bill told her. ”But, of course, you have them insured?”

”No, I have not,” Sidi replied.

You should neglect that no longer,” said Diamond Bill. Then, he paused for a second, as if he’d just been struck by a thought. ”Why not let me have them?” he asked suddenly. ”I’ll take them and have them insured. It will save you the trouble and it will guard against possibility of substitution, because I can spend the whole day at the matter and see to it that when they are appraised there will be no underhand work.”

Sidi, delighted by this kind offer by her dear friend’s husband, immediately removed the pearls and handed them over.

She never saw them again.

The next day, Diamond Bill Barrett hopped on a fast steamer bound for the U.S., leaving his young pregnant wife and her too-trusting friend behind in Europe and disappeared.

(The abandoned Alice appealed to her parents for help, and they came to her rescue; after her baby was born, she quietly secured a divorce. The baby died in infancy 10 months later.)

Naturally, the police in London and the U.S. got busy trying to track down Diamond Bill. Eventually the cops in Los Angeles found him, living there under a pseudonym and working now in the movie industry – or, rather, trying to; he was, as historian Ken Bilderback puts it, ”waving around wads of cash, trying to arrange a movie to produce.”

Brought in for interrogation, Bill deployed his legendary charm, claiming that he knew nothing about Sidi’s pearls, although she’d shown them to him and he had admired them. And as for the alias he was living under, well, he explained, he’d adopted the pseudonym not to dodge the arm of the law, but merely in order to get solidly into character for a movie he was working on.

The charm worked like it usually did, and, when the London police were a little slow in issuing a warrant, the L.A. cops let him go – much to Sidi’s subsequent disgust. Because, of course, he then promptly disappeared again.

Not much is heard from Diamond Bill after this. In 1932 he was arrested in Brazil for counterfeiting, and sentenced to a six-year prison stretch. By that time he was, of course, a little too old to be sweeping wealthy debutantes off their feet, and apparently the ”printing business” was his attempt to find a new racket. He died of old age in 1963 – broke, of course, and living on his Army pension and social security benefits – and was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

Looking back over his life, it’s hard not to think the biggest mistake Diamond Bill ever made was burning his bridges with Sidi Wirt Spreckels, who was clearly his soulmate.

Sidi’s romantic resumé is even wilder than Bill’s.

While a student at the University of Kansas, she got engaged to marry a Brazilian nobleman; but then she ran out on him on their wedding day, and got married to a newspaper reporter in an automobile while literally running from her angry ex-fiancé and his family – apparently the preacher was in the passenger seat. This marriage ended just a few days later, and after that she went into show business as a cabaret singer.

In 1918 she swept sugar-fortune heir Jack Spreckels off his feet, married him – very much against the wishes of his family – and received the $120,000 string of pearls from him as a wedding gift.

The marriage soon soured, and she filed for divorce shortly after returning to the U.S. to pursue Diamond Bill and her stolen pearls; but Jack died in a car wreck before the divorce could be finalized.

A year or two later, Sidi married a Turkish prince, and apparently finished her remarkable career as an Anatolian princess.

But, this is perhaps the most interesting part of the whole story: What if the two of them actually were in cahoots?

The pearls that Diamond Bill nicked were not paid for, and Tiffany’s of London made several unsuccessful attempts to hold Sidi responsible for their disappearance. Eventually they collected the $80,000 balance owing on them from the Spreckels family; but if they hadn’t been stolen from her, Sidi would probably have had to give them back.

Did she and Diamond Bill just happen to meet in London? Or did Diamond Bill actually journey to London to meet her, to do a mutually profitable favor for an old friend and partner-in-crime?

As clever as those two clearly were, we’ll never know the real story for sure. But Sidi’s protestations of anger and bitterness against Bill in subsequent newspaper articles have the distinct flavor of a lady who ”doth protest too much.”

Sources: Law and Order at the End of the Oregon Trail, a book by Ken and Kris Bilderback published in 2015 by Ken and Kris Bilderback; archives of the Portland Morning Oregonian for 1911, 1920-1922, and 1932

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. His book, Heroes and Rascals of Old Oregon, was recently published by Ouragan House Publishers. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.