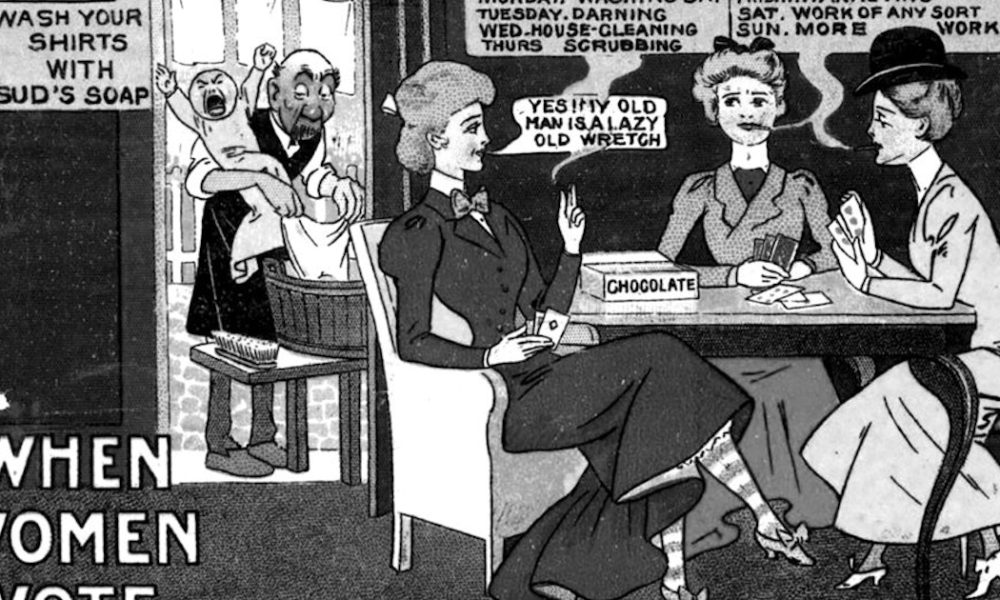

A typical piece of anti-suffrage propaganda masquerading as humor, from the 1910s. Image provided/Smithsonian

A typical piece of anti-suffrage propaganda masquerading as humor, from the 1910s. Image provided/Smithsonian

It was around 2 p.m. on Election Day, in December of 1916, that Umatilla’s mayor, E.E. Starcher, first discovered that he was not running unopposed for re-election.

That’s when someone mentioned to him that his wife, Laura Starcher, was running a write-in campaign against him.

Mayor Starcher thought this was a fine joke, of course. ”I felt secure enough,” he told a reporter from the Pendleton East Oregonian, ”but I got busy at once. Everywhere I went among old adherents I found they had voted for my wife, and I thought all the time they had voted for me!”

By the time the polls closed that evening, he had lost in a landslide, 26 to eight; and the City of Umatilla had elected a full slate of women to all its elected positions.

Not a single man was elected – or, rather, re-elected, since the men they defeated had all thought they had been running unopposed until five hours before the polls closed.

In addition to Starcher, the voters of Umatilla elected Lola Merrick as city treasurer; Stella Paulu, Florence Brownell, Mrs. H.C. Means, and Gladys Spinning as city councilors; and Bertha Cherry as city recorder.

Although Umatilla even then was a tiny town – population roughly 200 – it was a remarkable coup.

Women had just won the right to vote in Oregon in the 1912 election, and were still not allowed to vote in national elections – that wouldn’t change until 1920.

And, of course, the country was being treated to a flood of anti-suffrage propaganda courtesy of business interests – especially the liquor industries – that believed they would suffer if women were able to vote.

Typical of this sort of propaganda were ”joking” postcards showing pathetic-looking men in house dresses, holding a wailing baby in one arm and scrubbing laundry on a washboard with the other, while a mannish and masterful-looking woman in trousers and waistcoat puffs on a cigar and tells him he missed a spot.

Naturally, there were some overtones of this style of ”joking” in newspaper coverage of the event.

”Though the women who won the election are still keeping secret their plans, it is said there is no doubt that the town will have a man as Marshal for the simple reason that among the duties of the said Marshal are the care of the City Hall, as well as doing the janitor work about the institution, and the women elected … propose that no woman shall have to do that menial labor,” a Portland Oregonian reporter wrote a few days after the election, with an almost audible sneer.

This claim is contradicted by every other news report I could find, by the way – including, ironically, another article published on the very same page under the headline, ”UMATILLA MAY HAVE WOMAN POLICE, TOO.”

A few days later, Mayor-Elect Starcher told the Pendleton East Oregonian she’d reached a definite decision about that.

”That official will be a woman,” she told the reporter. ”We will not leave the enforcement of our laws to any man, because past experience has proven the laws will not be strictly enforced.

”The men as yet consider the recent election as a huge joke,” she told another newspaper correspondent, ”but the women are taking the matter seriously. I have not mapped out my career for the future, but our main idea is to put the town government on a good and sound financial basis.”

The election-day coup had its origins in a card party held at Treasurer-Elect Brownell’s house a month or two before. The ladies at the party got to talking about the sad and dwindling state of Umatilla’s appearance; it looked, they all agreed, like a town in terminal decline. It was especially bad because a month or two before the town council had canceled its contract with the power company to provide street lights.

And the city officials seemed to be uninterested in doing anything about it.

The ladies were indulging in the usual desultory musing about how much better things would be if women were in charge, when, at some point, one of them tumbled to the fact that – thanks to the results of the last major election – they didn’t have to just speculate any more.

They drew up a plan on the spot, selected candidates from among themselves, and got busy.

Mrs. Brownell’s husband, a local railroad executive, was in on the plot, and he undertook to discreetly spread the word among railroad men – those who could be trusted not to spill the beans.

The ladies got busy spreading the word among the wives and daughters of the town at tea parties and social gatherings. And they kept things so quiet that the men who fancied themselves to be in charge of the town knew nothing until Election Day.

When Election Day came, it was all such a huge surprise, and such a clean sweep, that headlines were made nationwide. Umatilla’s election was dubbed ”The Petticoat Revolution.”

Not surprisingly, far-distant journalists, most of whom assumed this was some sort of suffragette stunt, felt free to impose their own dramatic spin on the story.

Some didn’t stop at spin.

An article in the notorious New York Herald testified that ”Strong men wriggled and flushed under the biting satire of Mrs. Starcher’s inaugural address, which was largely devoted to a skillful dissection of mere man’s foibles, weaknesses, faults, shortcomings, vices, general uselessness, and worthlessness. But they sat and ‘took their medicine.’”

And readers of the Herald were free to believe that, and to trust that the newspaper had actually gone to the trouble and expense of sending a reporter all the way out to Oregon to cover the mayor’s race in a tiny town none of them had ever heard of, even though nobody would ever have been the wiser if they had stayed in Manhattan and just made the story up.

Which, of course, is exactly what they did.

Laura Starcher stepped down as mayor eight months into her term for health reasons (represented by some reporters as a ”nervous breakdown,” from which they imply that the cares of public office drove her to the brink of madness) and was replaced by Stella Paulu, who went on to easily win re-election in 1918.

The ladies ran the town for four years; from 1916 to 1920 the town had a four-two majority of women on the City Council and was led by a female mayor.

Newspaper reports at the time and thereafter implied that the ladies were in over their heads and barely hung onto power, straggling through the next four years without getting much done.

But Hartwick College historian Shelley Burtner Wallace, who dug into the city records and courthouse documents, found out that was not the case at all.

In fact, the ladies did an excellent job of turning things around at City Hall. They brought back the street lights and put water meters on all the residences. They cracked down on public nuisances like dogs and chickens running loose around town, and they took prompt action to put the city’s streets and sidewalks back in presentable order.

And they sent many a-letter to residents of the type that modern homeowners would associate with a fairly aggressive homeowners’ association. The ladies had launched their campaign because they saw their town looking progressively more and more slummy, and getting the town to look properly respectable was Priority One.

A homeowner who left some construction material out in the yard too long got a letter from the mayor’s office ordering him to ”remove the toilet from the yard.” Another got a letter ordering him to ”clean up the shed,” and several got notices to clear out trash. Those who ignored such notices quickly learned the ladies weren’t bluffing. Promptly after the deadline named in the letter, city contractors would be on the scene taking care of the problem, and the homeowner would be duly billed.

To help encourage things not to get to that point, though, they instituted a garbage service, paid for by the city. They also founded a library and a fire district. They instituted a speed limit and parking ordinances and installed warning signs at railroad crossings. They drew up plans for a campground for tourists, downtown water fountains, and a pesthouse.

In 1920, the coterie of ladies who had taken over Umatilla and turned it into a respectable and well-groomed hamlet retired from public life.

Apparently feeling that their mission had been accomplished, they declined to run for re-election and returned home to enjoy the little piece of heaven they’d helped create, leaving a standard-issue all-male city government to carry on.

Sources: ”Umatilla’s ‘Petticoat Government,’” an article by Shelley Burtner Wallace published in the winter 1987 issue of Oregon Historical Quarterly; public lecture by historian Darrell Jabin, November 2015; archives of Portland Morning Oregonian and Pendleton East Oregonian, December 1916 of a phenomenally clever (or lucky) hoaxer.

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. For details, see http://finnjohn.com. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.