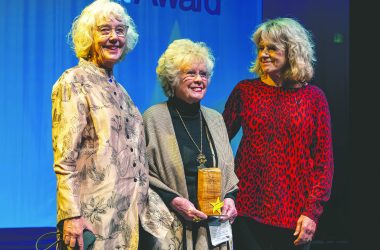

This political cartoon, by Thomas Nast, ran in Harper’s Weekly in 1871. It nicely illustrates society’s attitude toward those who advocated ”free love” – in this case, Victoria Woodhull. The woman is depicted struggling under the heavy burden of a drunken husband and several children, but saying, ”Get thee behind me, Mrs. Satan; I’d rather travel the hardest path of matrimony than follow our footsteps.” IMAGE: OSU LIBRARIES

This political cartoon, by Thomas Nast, ran in Harper’s Weekly in 1871. It nicely illustrates society’s attitude toward those who advocated ”free love” – in this case, Victoria Woodhull. The woman is depicted struggling under the heavy burden of a drunken husband and several children, but saying, ”Get thee behind me, Mrs. Satan; I’d rather travel the hardest path of matrimony than follow our footsteps.” IMAGE: OSU LIBRARIES

The editors and writers of Anarchist-Communist newspaper, The Firebrand, published in Portland and distributed nationwide from 1895 to 1897, surely expected to get some resistance from the establishment. They may even have expected to be arrested, possibly even charged with sedition or treason.

But they surely didn’t expect that when their publication was shut down, it would be for criticizing the institution of matrimony.

That’s what happened, though. The wide-open town of Portland reacted to their strident advocacy of revolution and regime change with a collective yawn; but when they started advocating ignoring the laws of marriage, well, that was going just a little too far.

The Firebrand was a product of what may have been the worst depression in American history, as measured in per-capita human misery. This depression, usually referred to by the misleading moniker ”Panic of 1893,” got its start in February of that year when a revolution broke out in Argentina, the most prosperous and stable country in South America at the time. Spooked, European investors pulled their money out and, seeking a safe place to park it while they awaited further developments, started buying up dollars.

The U.S. dollar was at the time rigidly pegged to gold. So, the more dollars the Europeans bought up, the more scarce dollars became – and the more valuable they got, and the more attractive they became to foreign investors. At the same time, the rising dollar value made everyone who had a dollar less inclined to spend it, and debtors more likely to default on their mortgages.

One thing led to another, and by the end of that year, the U.S. was plunged into depression.

Very few people today realize how bad it was, that depression; the Great Depression of the 1930s absorbs most of the attention. But, the mid-1890s were the last time large numbers of American women living in urban areas were forced to choose between prostitution and starvation. Among other unemployed Americans, the lucky ones were able to trade their dignity for a meager meal at a soup kitchen once or twice a day or poach animals and fish; the unlucky ones died of illnesses their hunger-weakened bodies couldn’t fight off.

To make matters worse, the unemployed and starving had to watch wealthy upper-class citizens strutting callously by as they suffered; situations of the worst and most grueling privation coexisted side by side with wealth and privilege. It was like the first few scenes from ”Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” the book by Roald Dahl.

Many well-off citizens tried to pretend the problem was one of morals rather than economics – that the unemployed were jobless because they were lazy – and the ”robber barons” made no secret of the fact that they didn’t care who lived or died.

Naturally, these attitudes inspired some resentment.

By 1895, it had been so bad for so long that the American working class was a demographic powder keg. Forces of reform grew stronger as the economy grew weaker: the free-silver movement sought to bolster the gold stocks, to stop the dollar’s climbing value; Populist politicians sought to claw power away from the smoke-filled room with projects like the Oregon Initiative and Referendum System; and support for journalistic ”muckrakers” exposing the corruption of the powerful was strong and growing.

But to the small group of dedicated journalists producing The Firebrand in Portland, all of that was useless – like performing cosmetic surgery on a patient dying of cancer.

Henry Addis and his tiny group of colleagues – lapsed Mennonite Abraham Isaak and his family, and the elderly ex-Quaker Abner J. Pope – called themselves ”Anarchist-Communists,” but the meaning of that term at the time was closer to what we know today as libertarian.

The Firebrand was an interesting publication, because although Addis and his crew really didn’t know what they were doing, they had been interested observers of previous anarchist movements and they’d learned a great deal from their mistakes. So although freelance articles poured in from radical writers across the country, those that advocated covert operations and sabotage, or authoritarian devotion to some charismatic leader, or the use of bombings and assassinations, were slipped quietly into the trash.

The Firebrand’s political and editorial positions were fairly well defined by its masthead motto – ”For the Burning Away of the Cobwebs of Ignorance and Superstition,” superimposed on a graphic of the state capitol building and a church steeple connected by a spiderweb occupied by a fat spider holding a bag of money – and by the sarcastic definitions of pillars of Gilded Age society which it published: ”CLERGY: The paid tools of the rich to keep the poor divided on religion and unanimous in their respect for the state. FRAUD: Shrewdness in business. MARRIAGE: Legalized prostitution and enslavement of the sexes. ARMY: Licensed murderers. CONGRESS: A body of men organized to break laws and make debts.”

All of this probably resonated pretty well with working-class Portlanders, and it seemed also to play well in the crews of bachelors in the mining and logging camps across the state. But none of those people had much money to spare, and the ”Firebrand Family” always had great difficulty getting enough to eat. They moved their operations into the country outside of town where they could do some subsistence farming, keeping a cow and some chickens; they spent days in the Portland hills picking wild blackberries to can, to get them through the winter; they picked hops for a little seasonal side income; and they tried, and failed, to start a dairy farm.

Toward the end the plan was to acquire a small farm on the lower Columbia and set up a commune there. But before that could be done, the cops moved in.

It wasn’t The Firebrand’s political position that brought on the trouble, though. It was the publishers’ advocacy of what was then called ”Free Love.”

Free Love was an idea that covered a wide range, from ”get the state out of the marriage business” to total sexual freedom. What all these positions had in common was, they violated the (patently unconstitutional) Comstock Laws, violations of which were punished with jail time.

The Firebrand had freely published articles arguing that marriage should be abolished, along with articles like ”Plain Talks about the Sexual Organs” and ”Teaching Sexual Truths to the Children.”

One particular article, by writer Oscar Rotter, advocated ”variety” in personal relations. This sparked a lively debate among advocates of monogamistic free love (basically, common-law marriage) and those who – like the editors of The Firebrand – felt that other people’s choices to be slutty or not were nobody’s business but their own and certainly not the state’s. The debate went on for several months.

This may be what caught the attention of the postal authorities. In any event, something did, and one day in 1897 as Abner Pope was preparing the last issue for mailing, a deputy U.S. marshal arrived and arrested all three of them.

The ensuing trial was rather a disaster, primarily because the defendants’ attorney was extraordinarily incompetent. Judge C.B. Bellinger was so exasperated that, after the jury brought in a verdict of ”guilty,” he made a point of telling the defendants that he would support a request for a new trial.

Pope seemed determined to take as much of the ”blame” as he could, and Addis and Isaak were happy to oblige. This, as historian Schwantes points out, probably had a lot to do with the fact that the city jail was very comfortable compared with the accommodations the ”Firebrand Family” had been making do with before his arrest.

Remember, he was very old; and he had just gone from a winter of subsisting on grubbed-up roots, canned blackberries and the occasional pot-shot squirrel, to three square meals a day in a building with steam heat and indoor plumbing.

In the end, Pope was sentenced to four months, and charges against the other two were dropped. But the paper was never restarted.

In the end, the ”Firebrand family” must have been a little nonplussed to find that one could shout all day about revolution and regime change, but suggesting that the state should stop prosecuting people for unauthorized sexual activity got them sent straight to jail.

Well, in 1897, that was Portland.

(Sources: Schwantes, Carlos. ”Free Love and Free Speech on the Pacific Northwest Frontier: Proper Victorians vs. Portland’s ‘Filthy Firebrand,’” Oregon Historical Quarterly, fall 1981; Cornett, William. ”The Firebrand,” The Oregon Encyclopedia, oregonencyclopedia.org)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. For details, see http://finnjohn.com. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.