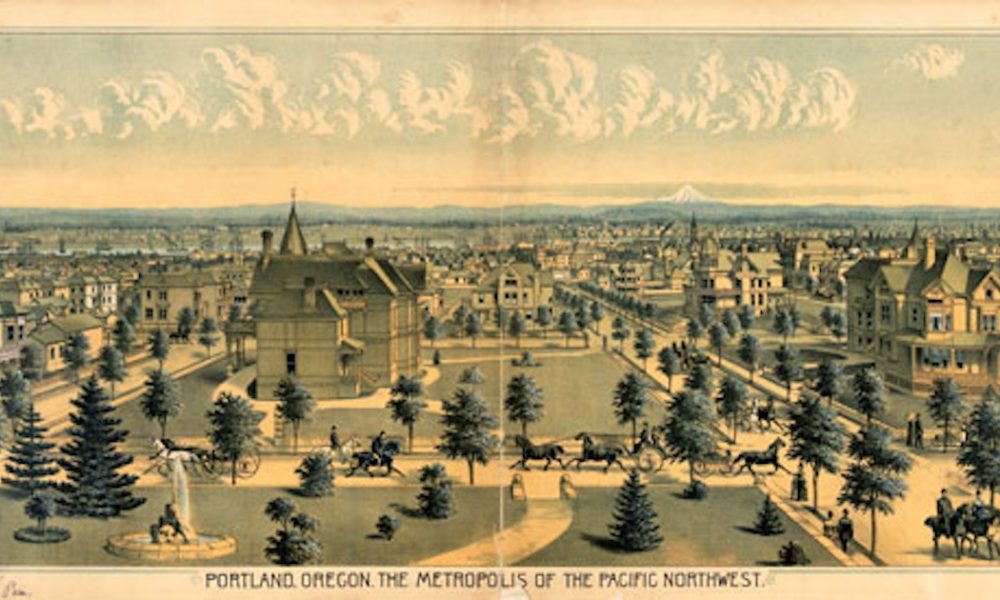

This panoramic lithograph shows the city of Portland as it appeared around the time of John W. Murray’s shotgun murder of his brother-in-law. It was published in an 1888 edition of The West Shore magazine. IMAGE PROVIDED/UO LIBRARIES

This panoramic lithograph shows the city of Portland as it appeared around the time of John W. Murray’s shotgun murder of his brother-in-law. It was published in an 1888 edition of The West Shore magazine. IMAGE PROVIDED/UO LIBRARIES

The late 1880s in Oregon, and around the country, saw a substantial rise in the number of murderers who tried to invoke the ”Unwritten Law” to justify their crimes.

The ”Unwritten Law” is the idea that if a man (yes, man; the ”law” didn’t apply to women) truly believed that another fellow was trying to ”break up his happy home” by getting intimate with his wife, or was trying to ”ruin” a young female relative by seducing her, he was not only justified in murdering the ”home-wrecker” but morally obligated to do so.

The belief was that ”no jury in the land” would sentence a man to hang for having ”defended his home” or avenged the honor of his daughter, niece, sister, etc., because although the written law said murder was always wrong, an unwritten moral code demanded it. And for a time this worked in court, as you’ll know if you’re a longtime reader of this column; we’ve discussed several high-profile Unwritten Law cases in Offbeat Oregon History articles past.

The Unwritten Law didn’t come out of nowhere. Although the widespread enthusiasm for this law wouldn’t appear until the mid-1890s, it was being used to justify homicide throughout the 1800s and even before – with a disturbing degree of success.

But in order to successfully claim the protection of the Unwritten Law, there were some requirements that a man had to meet. Those requirements constituted a very low bar; a fellow might be a wife-beater and/or a philanderer without worrying too much about ruining his chance of being acquitted after murdering his wife’s boyfriend.

But he did have to make sure that the man he murdered was not his brother-in-law. And also, it was pretty important that he not be a bigamist who had abandoned a wife and several children back east to slink away to the West Coast and start a new family.

In early 1884, John W. Murray failed to clear both these bars, and in consequence, on Feb. 13, roughly a year later, he found himself standing on the gallows scaffold ready to answer for his crime.

The trouble started on Jan. 5, 1884, at the Foresters’ Ball, held at the Masonic Center in Portland. Murray, dressed to the nines, arrived and spotted his estranged wife, Annie, there with her brother, Alfred Yenke.

John and Annie had been married for four years, and had a 3-year-old daughter. But the marriage had been stormy, and three weeks earlier – just before Christmas – Annie had taken the baby and moved back in with her parents. A divorce, on the grounds of excessive cruelty, was probably in the offing.

John seemed to be in the mood to smooth things over now. He approached Annie and pleasantly asked if she’d like to dance.

She turned him down. ”I do not think we should be seen together,” she told him. ”I would prefer not to associate with you any longer.”

John was instantly furious. ”I’m going to watch you,” he raged. ”If you go home with anyone I’ll have you both arrested.”

Annie turned her back on him, leaving him still further incensed. They didn’t speak again that night; and at around midnight, when John returned to the boardinghouse where he now lived alone, he was still simmering. He had probably had a lot to drink as well.

His landlady was still up, and had also been at the dance. John got out his shotgun and threw it down on the table. ”Here is the old gun,” he raged. ”I am going to shoot any damned man that goes home with Annie, and then I am going to shoot her.”

The landlady pleaded with him not to do it – for his daughter’s sake. ”Why do you want to kill her away from your beautiful little girl?” she said.

John seemed chagrined by this thought, and seemed to agree. But when he left the building a few minutes later, he took the shotgun with him.

Some time later, John spotted Annie. She was visiting with one of the other couples outside the dance. Then a man joined them, and the couple left going one way while Annie and the man strolled down the street toward Annie’s parents’ home.

They made it about two blocks before John caught up with them. ”Now I’ve got you!” he shouted. The man turned – and caught the full charge from both barrels square in the chest. The blasts knocked him off the plank sidewalk and into the mud of the street.

That seems to have been the point at which John realized he’d just murdered his brother-in-law. It was Alfred Yenke who was lying there in the mud looking up at him with fast-glazing eyes.

At the murder trial, John’s attorney tried very hard to demonstrate that he was crazy – that, having already had some insanity in the family, the prospect of having his home broken up had driven him over the edge and out of his right mind. Granted, a terrible mistake had been made in thinking his wife’s brother was a marauding Lothario, but that mistake had led to temporary madness which should not be punished with death.

Against that, the prosecution brought forward some credible evidence that John might have actually intended to murder his brother-in-law all along, and that all that posturing and fuming about Anna ”going home with someone” was intended to give him cover for the deed. He had asked his landlady’s daughter to keep his dog indoors that night, something he had never done before; the implication was that he feared the dog would run to greet Anna and Alfred and alert them to his presence, at which point they might see the shotgun in time to escape.

There were also a couple witnesses to whom John apparently spoke too freely at the dance, one of whom remembered John pointing out Alfred and saying, ”I’ll get even with the [expletive redacted from original newspaper article] tonight. I’ll show him how the work is done.”

The verdict, when it came in, was guilty of first-degree murder.

John’s attorney appealed to the state Supreme Court, resulting in a nearly year-long delay of the execution. During this time, word filtered back from Amsterdam, New York, that John was a bigamist.

”He was known there as Amsterdam Jack, and he fled that part of the country about eight years ago, leaving a wife and two children,” the Portland Evening Telegram reported. ”She is working for the support of herself and children in one of the knitting mills at that place.”

Although the news arrived too late to affect the outcome of the trial, it may have had some impact on the decisions of the appellate courts and the Supreme Court. Eventually the Supreme Court denied the motion for a new trial; the judge re-sentenced John Murray to be hanged; and on Feb. 13, it was done.

As a side note, the gallows used to hang John W. Murray was equipped with an electrically-controlled trap door, which was sprung open with the push of a button. It was the first use of electricity in an execution in Oregon history, and possibly in American history as well.

(Sources: Goerdes-Gardner, Diane. Necktie Parties: Legal Executions in Oregon 1851-1905. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton, 2005)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. For details, see http://finnjohn.com. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222