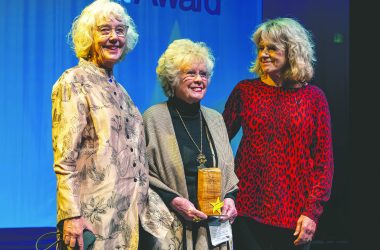

A line of Tillamook Guerilla Rifle Club members practice taking up a battle position behind a berm in March 1942, in this photo by an Oregon Journal photographer. IMAGE-OREGON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

A line of Tillamook Guerilla Rifle Club members practice taking up a battle position behind a berm in March 1942, in this photo by an Oregon Journal photographer. IMAGE-OREGON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Early 1942 was a really nerve-racking time to be an Oregonian – especially if you lived on the coast.

The United States had just gone to war against a country that was already famous for being able to deliver large amounts of force anywhere within 600 miles of its aircraft carriers. No other country in the world, at that time, was better at surprise attacks; and no other country in the world could bring those attacks to bear farther away from its home shores.

So although Japan itself was thousands of miles away on the other side of the Pacific, there was a real sense in coastal Oregon and Washington that the Pacific might as well be a very large river for all the protection it would afford, if the Japanese decided to invade. Oregon and Washington were, in a real sense, the front lines.

So there were plenty of heartburn pills sold in Oregon drugstores when, a few months into the war, the Oregon National Guard got called up to go fight in Europe, leaving the state wide open and defenseless.

In Tillamook, a man named Stewart P. Arnold had an idea for a way to do something about that.

Arnold was a First World War veteran, and had lost his sight in combat. But he seems to have lost none of his fighting spirit. He arranged the organizational meeting of something called the ”Guerilla Rifle Club” at the Pleasant Valley Grange on March 5, 1942, and a total of 69 local men signed up.

The plan was for this loose association of local men, packing their own hunting rifles, to be ready on a moment’s notice to resist a Japanese invasion.

Their organization was paramilitary, with officers elected by the membership, militia-style, and a military chain of command. At the organizational meeting, Arnold was elected commanding officer, with the ”rank” of colonel; and the membership elected a captain (Art Sperber) and a first and second lieutenant (Earl Clarine and Ralph Blum) as well.

But they were definitely not an Army unit. They were civilian volunteers, with no uniforms, sponsored by no government. If captured by an invading force, they would be treated as fifth-columnists, not entitled to the protections of the Geneva Convention.

That was fine; the men understood that. They also understood that if the Japanese actually invaded Oregon, not having the protections of the Geneva Convention would be the least of their worries.

Within a month, the Tillamook County Guerilla Rifle Club had swelled to more than 1,000 members and attracted national attention.

”(There are) snuff-dipping mackinawed men from the forests; ruddy, overalled farmers of sturdy Swiss stock; pale businessmen from the little towns,” wrote a Time Magazine reporter in the March 30 issue. ”They had no uniforms, did no drilling, furnished their own guns and ammunition for target practice. But they were dead shots and they were ready to shoot.”

”I think a lot of guys in the Guerrillas were guys who couldn’t get into the military, or were disabled for one reason or another,” Garibaldi historian Jack Graves told the Tillamook Headlight-Herald’s reporter in 2010, ”and older guys, including ones who had already served their time in the military.”

There were some younger lads as well – 16-year-old boys too young for Army service, but as good with a .30-30 as any 25-year-old Marine.

”If the Japs try to land in the bays or inlets – Netarts, Tillamook, or lesser coves – they will find guerrillas on cliffs, sandspits and in the bogs – using their own ammunition and rifles,” Colonel Arnold told the Headlight-Herald reporter. ”Our motto is, keep your guns cleaned and oiled, and your powder dry.”

It was more than just that, though.

”My dad (Roy Graves) told me they had mined all the bridges that connected Tillamook to the (Willamette) Valley,” historian Graves told the Headlight-Herald reporter. ”There were teams of two to three men assigned to each bridge.”

Especially after Time Magazine’s article came out, the idea of forming guerilla militia companies spread wildly across the state. A similar group sprang up almost immediately in Lincoln County. A group calling itself the Bushwackers had already formed in southeast Portland, three months before; another guerilla club now formed in Independence; and, across the state, as April dawned, the guerilla-militia movement started taking Oregon by storm.

Meanwhile, the Oregon State Guard was growing nearly as quickly. Formed in 1940 as a military force answering directly to the governor, the state guard was the logical organization to take on what the guerillas were doing.

The State Guard got scant support from Washington, D.C., until word got out about the guerilla companies. At that point, Army leaders started pondering worst-case scenarios involving random gangs of poorly-trained armed men running around the countryside looking for Japanese soldiers to kill. It wasn’t hard to imagine ways this could turn out very badly, and the Army had no way of knowing what kind of training these guerillas were getting. Soon the pressure was on Governor Charles Sprague to rein them in – and Washington was suddenly in a far more generous mood as regards rifles, ammunition and training supplies.

Sprague, who had been supportive at first, now started encouraging the guerillas to join forces with the state guard.

”One thing made clear in this war is the value of guerrilla fighting; and our local fighters, familiar with the terrain, can be of great value in repelling the enemy,” he wrote, in a press release on March 17. ”They should be enrolled in a military body, however; otherwise they would not be entitled to the rights of prisoners of war, if captured, but would be subjected to immediate execution. They should also be regularized for training and for proper coordination with regular troops.”

In May, the federal government, dissatisfied with the pace of absorption, actually ordered all the guerilla clubs to disband or be absorbed into the state guard. Most of them, by this time, had done so; but ”Arnold’s Raiders,” the biggest of the bunch, still held onto its independence.

An awkward showdown was avoided by the expedient of redesignating the Tillamook County Guerilla Rifle Club as a non-military organization, and it continued as an independent club.

Ironically, it was the following month that the Japanese came as close as they ever would to actually invading the mainland U.S., when the submarine I-25 hove to off the mouth of the Columbia and shelled Battery Russell. That, of course, was a county away from the Tillamook Guerillas’ home base; but it’s a safe bet that some of Arnold’s Raiders were on their way northward, rifles locked and loaded, the minute they got the word – just in case.

(Sources: ”Tillamook Guerillas Mobilized for an Invasion in 1942,” Tillamook Headlight-Herald, 07 Apr 2010; ”The National Guard is Off to War: Who Will Protect Us Now?”, Life on the Home Front (virtual museum exhibit), State Archives, Oregon Secretary of State; Lindberg, Andy, and Kenck-Crispin, Doug. ”KAOH 10.7: The Tillamook Guerillas,” Kick Ass Oregon History podcast, 10 Sep 2017)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. For details, see http://finnjohn.com. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.