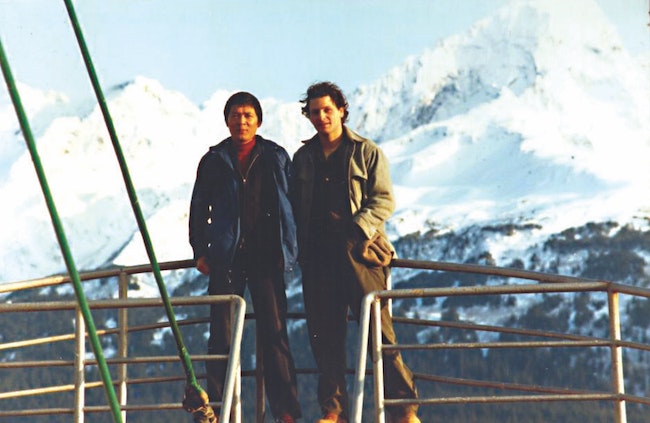

Above: The author, right, with the Captain and Fishing Master, on the Ebisu Maru. Below: Quantifying fear.

Above: The author, right, with the Captain and Fishing Master, on the Ebisu Maru. Below: Quantifying fear.

In November of 1982, I was in the Bering Sea, working as a biologist/observer for the National Marine Fisheries Service and assigned to a Japanese Long Line vessel, The Ebisu Maru. The ship was 170-feet long with a crew of 20, fishing the Aleutian Islands for groundfish. One thing you learn when fishing in the North Pacific and Bering Seas is that weather comes at you hard. You learn to ride out heavy weather that makes the worst day shown on The Deadliest Catch television show seem like a summer day on Dorena Reservoir.

This particular storm came across Siberia, and since we had daily weather maps, there was time to prepare. Typically, bad storms lasted three to four days, and unable to fish in heavy seas, the crew took to their bunks for a much-needed sleep.

Once the storm arrived, I spent the first day secure in my bunk, bracing my legs against the bed rails so as not to fall to the floor. This storm was unlike others I had experienced, steadily building in ferocity.

One of my responsibilities was to take weather and sea condition readings every day at six o’clock. The ship’s bridge sat 20 feet above the waterline, and waves were crashing down that were 20 to 30 feet above that. For the first time in my life, I wrote down Beaufort 10, only two steps away from a hurricane. The waves swelling and subsiding around us were close to 50 feet, and the ship rose and fell in troughs and peaks. The sea and sky were indistinguishable.

Fear crept into my mind as sleep became more a way of shutting down than it was restful.

I slept 17 hours the first day, but when I could sleep no more, I went to the bridge. During storms, the captain and fishing master took the helm for six-hour turns. The fishing master, who had fished and whaled in every ocean on the planet, calmly sat in the helmsman’s chair. He sang in Japanese, wearing a traditional fisherman’s bandana around his head. Each time a wave sent a harmonic vibration through the steel hull, the master looked to me and in broken English said, “My ship is strong!” If he was frightened, it didn’t show. I did not want to show my fear, so I put on a good face, but I thought I was going to die in the steel grey Bering Sea, north of the Aleutians Islands south of the Pribilof Islands.

On the second day of the storm, I rested in bed while visualizing the welders as they had fabricated the hull of the vessel. I followed every seam as if counting stitches in a wound. Starting at the bow, I followed the seams to the stern. When that ended, I imagined there were Shachi (Japanese for killer whales) guarding the ship against danger.

It has long been lore that sailors may presage their death at sea, even accepting its inevitability. That may sound romantic, and it makes for a good tale, but at the moment when you confront death, if there is any choice in the matter, it never hurts to pray for your survival. I looked out of the porthole and said if I am to die here, so be it, but I didn’t want to die, and because of the calm of others and a deep mystical sense of my fate, I knew we would survive the storm. Full disclosure, I did a little bargaining by pledging that I would never go to sea again if I survived.

The storm continued, but on the fourth day, the ocean calmed, and soon we were fishing again.

Three weeks later, I returned to Seattle, and except for a short sail between Newport and Reedsport, never far from land, I have honored my pledge. Though even on that short trip, I felt the fates weighing the fidelity of the promise once made.