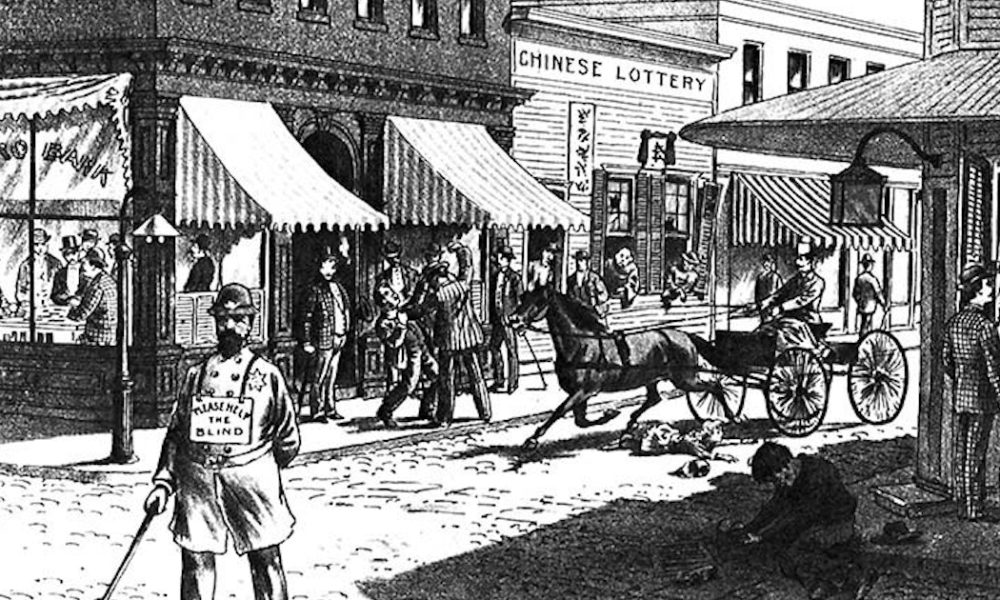

This cartoon was published in The West Shore in 1889 as a criticism of the quality of policing in Portland. The woman in the window on the extreme right is a prostitute negotiating with a prospective customer. It is possible, if not very likely, that this cartoon was drawn with the Carrie Bradley case in mind. IMAGE: The West Shore

This cartoon was published in The West Shore in 1889 as a criticism of the quality of policing in Portland. The woman in the window on the extreme right is a prostitute negotiating with a prospective customer. It is possible, if not very likely, that this cartoon was drawn with the Carrie Bradley case in mind. IMAGE: The West Shore

One of the most enduring and appealing tropes in popular fiction is the ”Femme Fatale,” like Brigid O’Shaughnessy in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon. Assertive, sexy, and utterly free from the soft bondage of conscience, she plays the men around her like pianos, getting whatever she wants and leaving them stranded afterward gasping for air like fresh-caught fish flopping on the dock.

Usually, in the old hard-boiled pulp stories and noir films, she comes to a bad end – as O’Shaughnessy does, more or less. But occasionally she doesn’t, and when the Femme Fatale is done right, it’s impossible not to root for her. She’s taking on the 1930s ”man’s world” like a Samurai taking on an enemy army. The odds are always against her; and when she beats those odds, and finishes the story sipping daiquiris on the beach in Togo rather than breaking rocks in the yard at Sing Sing, it’s a satisfying – and subtly unsettling – outcome.

But the Femme Fatale, like most really satisfying tropes in fiction, is based on real life. And arguably, the closest Oregon has ever come to a real-life femme fatale worthy of Hammett’s pen was in early 1880s Portland, in what today is known as the Tenderloin – in the person of a gorgeous, hard-eyed 28-year-old brunette who called herself Carrie Bradley.

CARRIE BRADLEY WAS a relative newcomer to Portland in 1881. She’d arrived in the late 1870s, probably from back east, when she was in her early 20s. By 1881 she was running a small bordello in the one-block red-light district that was regularly referred to in the Portland Morning Oregonian as ”the Court of Death” – the block bounded by Third and Fourth streets on one side and Taylor and Yamhill on the other.

That block had basically developed as the preferred location for high-end prostitutes in 1880s Portland. At the time, the majority of Portland’s hookers worked out of the old North End, the neighborhood along the waterfront north of Stark Street, known as Old Town today. In the North End, basically, anything went: public drunkenness, open gambling, prostitution, opium smoking, the shanghaiing of sailors, etc. ”Respectable” Portlanders tolerated virtually any level of vice so long as it stayed in the North End, where they never had to go and see it and could continue to pretend it did not exist.

Outside the North End, prostitution was tolerated if it was discreet. For instance, Lida Fanshaw, proprietress of the super-fancy whorehouse next door to the prestigious Arlington Club, had little to fear from Portland’s vice crusaders. Neither did Della Burris, whose parlor-house on Park Street was almost as fancy. In part that was due to their client lists – Fanshaw’s palace of sin was next door to the Arlington Club for a reason. But the main reason was, Fanshaw and Burris made it very easy for Portland’s churchgoing set to pretend they weren’t bordello madams. They did a brisk business, but they were very discreet about it.

”Carrie Bradley,” writes historian J.D. Chandler in his book, Murder & Mayhem in Portland Oregon, with fine understatement, ”was not discreet.” But then, perhaps she didn’t think she had to be. She was good friends with Portland Chief of Police James Lappeus.

The rest of the ”Court of Death” wasn’t very discreet either. It was comprised of a few bigger whorehouses like Carrie Bradley’s, plus one or two dozen ”cribs” – little cottages just big enough for a bed, a washbasin, and a window seat in which a girl could display herself to good advantage when a potential customer cruised by. These girls would be in their windows, displaying their wares and occasionally cooing a verbal invitation to an especially oofy-looking passerby, most of the time; and they were right in the middle of downtown, a block or two from all of Portland’s biggest churches, so the ”respectables” of the city couldn’t pretend they didn’t exist.

Most of the girls had enough sense not to be on display on Sunday mornings, of course; but still, everyone knew what the Court of Death was, whether any girls were visible or not. And pressure was growing to shut them all down.

Carrie Bradley was not helping to alleviate that pressure. Hers was a fairly dangerous business to patronize. Drugs and alcohol flowed freely in the downstairs parlor, where piano man ”Professor” Otto Jordan tickled the ivories ”and carefully minded his own business,” as historian Chandler puts it. Customers were plied with good brandy, sometimes spiked with laudanum; and for the really daring, there was chloroform that could be dabbed upon one’s upper lip. Customers would enjoy an evening of stimulating conversation and drug use in the parlor, then stroll upstairs with their ”dates” for the night.

And, once in a while, they would wake up the next morning in a different part of town, with a splitting headache and empty pockets. Carrie Bradley and her four girls were not above slipping a Mickey Finn to a wealthy customer and lifting his wad while he was sleeping it off.

And that seems to have been what happened to James Nelson Brown, a gent in his early 50s who had just moved to town from Freeport, Wash., with money in his poke.

BROWN HAD BEEN WORKING up in southwest Washington Territory, most recently as a timber cruiser; but in 1881 he decided to retire, sold his land for $4,000, and headed for Portland to live high on the hog on the proceeds. Checking into the National Hotel on Front Street at the foot of Yamhill, he set about ”making Rome howl,” as his contemporaries might have put it – drinking and gambling and, yes, patronizing prostitutes.

Including, of course, one of Carrie Bradley’s girls, a 21-year-old bombshell who called herself Dolly Adams. (The previous year, Dolly had called herself ”Belle Boyd”; no respectable hooker would ever dream of using her real name with customers. A girl’s real name was always a closely guarded secret, and usually the only way the general public could learn it was if she was murdered by a customer.)

Well, James Brown made the mistake of having $6 in his pocket when Dolly took him upstairs for the night; and when he woke up the next morning, it was gone. This enraged Brown, and he charged off to the authorities to see what could be done about it.

He was in luck. Multnomah County District Attorney J.M. Caples, who had been under pressure for some time to ”clean up” the ”Court of Death,” had been assembling evidence against Carrie Bradley for months. Brown’s allegation, he thought, would give him enough to prosecute, and, after shutting down Carrie’s whorehouse, he’d be able to roll up all the cribs with ease – the crib girls were solo practitioners, and had much less clout than Carrie did

Caples and Brown soon had a deal, and an arrest warrant went out with ”Dolly Adams” written on it – and Caples started preparing his case against Carrie and her whorehouse. Brown voluntarily anted up a $25 bond to reassure Caples that he wouldn’t disappear before trial; and then he waited for the gears of justice to turn, trying – at Caples’ insistent recommendation – to stay as far away from Carrie Bradley’s den of iniquity as possible.

Meanwhile, Caples told some of his law-enforcement partners what was afoot, and those partners probably included Chief Lappeus. Chief Lappeus, of course, promptly slipped the word to his friend Carrie Bradley that the heat was on. Carrie, after greasing the chief’s palm with a $500 bill in exchange for his promise to let her slip out of town if things got ugly, started making some plans of her own … and the plans she was making were the same ones Brigid O’Shaughnessy would have made, under similar circumstances.

The difference was, Brigid would have executed them with some modicum of competence. Carrie and her friends were going to bungle things very badly indeed.

We’ll talk about that in next week’s column.

(Sources: Murder & Mayhem in Portland Oregon, a book by J.D. Chandler published in 2013 by The History Press; archives of Portland Morning Oregonian, 12 Feb 1882 through 19 Jun 1882)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. His book, Heroes and Rascals of Old Oregon, was recently published by Ouragan House Publishers. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.