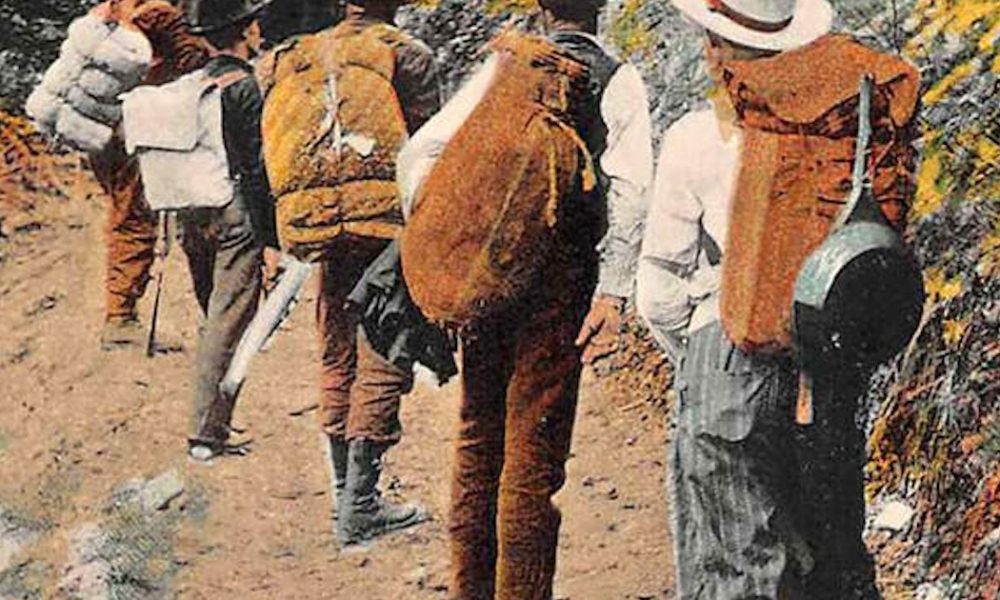

Prospectors out looking for gold in the Cascade Mountains, circa 1930. (Image: Postcard)

Prospectors out looking for gold in the Cascade Mountains, circa 1930. (Image: Postcard)

It was, most historians agree, the nadir of the Great Depression. The entire country had gone from singing ”Happy Days are Here Again” to ”Brother Can You Spare a Dime” in a few short months at the end of 1929, and in the three years that followed things had only gotten worse.

Now it was March 2, 1933, and the newly elected president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, had proclaimed a ”bank holiday.” All the banks, throughout the country, were invited to close their doors for a few days, so that everyone could cool off a bit. The fear was that bank runs, like the one in ”It’s a Wonderful Life,” would destroy the banking industry and with it, what was left of the economy.

Accordingly, Governor Julius Meier invited Oregon’s banks to take a three-day breather. And across the state, every bank closed its doors for a few days – with two exceptions. All the banks in the towns of Grants Pass and Baker City kept their doors wide open.

Why those two towns? Because in March 1933, at the worst moment of the Great Depression, those two towns were almost booming.

By the time the Depression got its teeth firmly into the scruff of the nation’s neck, official unemployment was sitting at 25 percent, and it seemed to most folks like that was sugarcoating it quite a bit. Those who had jobs fought to keep them, and took big pay cuts to do so. Those who didn’t have jobs knew they had a near-zero chance of finding one, even if they were in a high-demand industry.

Some took it on the road as hobos, sleeping under the stars and doing whatever odd jobs they could find in exchange for a meal. Others resorted to crime – squatting, poaching, petty theft – to stave off starvation.

But lots of them turned instead to the almost-forgotten lifestyle of the frontier gold miner, and waited out the depression on a legally staked and diligently worked mining claim. And more than a few of these claims paid out pretty well. Usually not well enough to sock away stacks of cash for a rainy day (or, rather, a rainier one), but well enough to live in what passed for good comfort by miner-49er standards.

”By early 1933, along with fish and wild game, the gold contained in the gravels of the Rogue River was providing a means of survival for countless local families,” writes historian Kerby Jackson in his book, ”Gold Dust”: ”At one time, it was estimated that over 1,000 men (mostly with families) lined the banks of the river between Galice and Gold Beach. This was an average of one person mining every 440 or so feet along the riverbank.”

There had already been a miniature gold rush under way on the Rogue; a couple months before the Depression kicked off, a rich decomposed-quartz vein was found in an abandoned mine along Mule Creek, yielding a jaw-dropping 200 ounces to the ton – which is to say, as Jackson puts it, ”$320,000 worth of gold in 20 five-gallon buckets of rocks.”

By 1933, that vein was long gone; but the miners who stuck around afterward had lots more company. Toiling with a pick, shovel and sluice box for a few cents’ worth of gold a day and living a rustic life in a knocked-up mountain shack was, to many, far preferable to a life huddled in a ”Hooverville” at night and waiting in bread lines all day, or tramping around the country being bitten by dogs and shot at by hostile farmers. Even if a claim yielded no gold at all, it was at least a place to live, and there were fish in the creeks, and deer in the woods, and acorns and wild camas roots to eat.

So thousands of unemployed Americans joined the gold rush, interested as much in having a place to call home as they were in striking it rich.

For many of the folks who did it, moving onto a mining claim seems to have been a good option. Enough gold was coming out of the fields, throughout the Depression, that the banks nearby were never actually in danger, and the local economies, while not exactly booming, weren’t in desperate straits either.

The Depression eventually dissipated, but gold miners were still doing well enough in the early 1940s that the federal government, in October 1942, felt it had to issue a wartime limitation order to get the miners working on something that would help win the war. With the stroke of a pen, it became essentially illegal to do commercial gold mining. The Depression-spawned gold-mining party was over, long before the music stopped; and by the time the government blew the ”all clear” in 1945, equipment had rusted or been stolen, mines had collapsed, mining towns had become ghost towns, and investors had taken their money elsewhere. The vast majority of mines simply didn’t bother to reopen, and very few of the small independent miners who left to go to war came back to their claims.

Which means there’s still plenty of ”gold in them-thar hills” today – waiting to get some more Oregon families through the next round of hard times.

(Sources: ”Gold Dust: Stories of Oregon’s Mining Years,” a book by Kerby Jackson published in 2011 by Six Guns Press; ”Prospecting for Gold in the United States,” a white paper by Harold Kirkemo published in 1991 by the U.S. Geological Survey)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. His book, Heroes and Rascals of Old Oregon, was recently published by Ouragan House Publishers. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.