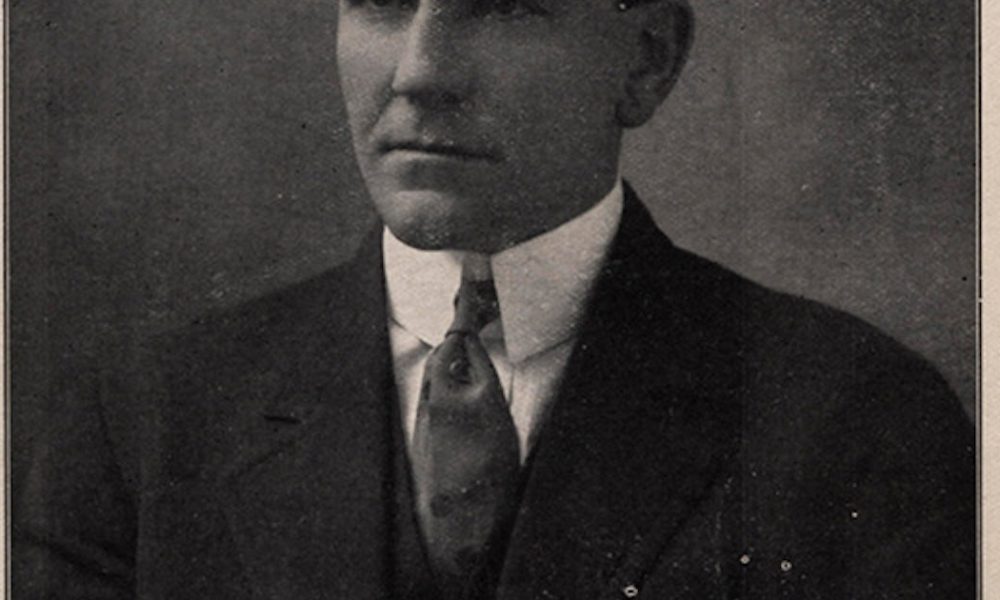

A poster for Oswald West’s 1910 gubernatorial campaign. His slogan, ”The Man Who Delivers the Goods,” reinforces the reputation he’d forged as an energetic man who gets things done, during the investigation of the school-land fraud and profiteering railroads. Photo provided/Oregon Historical Society

A poster for Oswald West’s 1910 gubernatorial campaign. His slogan, ”The Man Who Delivers the Goods,” reinforces the reputation he’d forged as an energetic man who gets things done, during the investigation of the school-land fraud and profiteering railroads. Photo provided/Oregon Historical Society

On your next visit to the beach, you might want to bring along a banana. One of these humble fruits played a small but important part in the historical chain of events that led to the state’s beaches becoming a birthright for all Oregonians.

More specifically, it was the banana peel – an item that has played an important role in hundreds of slapstick routines over the years. But rather than setting up a pratfall for a cheap laugh, this particular peel set up one of the most important governorships in state history – and set one of the most important of Oregon’s U.S. Senators on the path to power.

It was the year 1910, and a young lawyer named Oswald West was checking into a hotel in Portland. He was there on a mission: to convince Dr. Harry Lane to sign on as the Democratic Party’s candidate for governor.

West was an up-and-comer in the party, but he was not yet a particularly big deal. He’d gotten his start in 1903 when his boss, Asahel Bush, recommended him for the job of state land agent in the wake of the discovery of the school-lands swindle. Gov. George Chamberlain gave him the job, and over the next several years he clawed back what land parcels he could and helped prosecute such of the thieves and grafters as had left themselves legally exposed in their feeding frenzy – ”to save for our school children at least a small portion of their birthright,” as he put it. West dove into the project, and his 1904 report set up the land-fraud trials the following year.

Then, in 1907, Chamberlain named him to the newly formed railroad commission. The railroads had been taking full advantage of their effective monopoly, and popular resentment had reached the boiling point.

This job had given West a statewide reputation. But he was still a junior politico – not yet out of his thirties. The idea of running for governor himself had not occurred to him – or, if it had, he was enough of a team player to have dismissed it as something to work toward in the next go.

For now, he was concentrating on filling the top of the party’s ticket with the most viable candidate, and that – hands down – was Harry Lane.

Harry Lane was something like an older version of Os West. He was the grandson of Joseph Lane, the U.S. Senator who destroyed his career by running for vice-president with John Breckenridge on the pro-slavery Southern Democrats’ Presidential ticket in 1860.

But that apple had fallen a long way from its tree. The younger Lane became a medical doctor, and soon developed a reputation for treating poor Oregonians and then rebuffing their attempts to pay him. By 1910, he had a reputation for seriousness and for scrupulous incorruptibility. He’d been run out of his job as director of the insane asylum after publicly exposing a number of corrupt (but politically well-connected) contractors, who had been happily delivering barely-usable supplies and charging for first-rate goods; since then, he’d served on the state board of health and been elected Mayor of Portland. He was the state’s most well known and respected progressive reformer.

In 1910, Lane had just finished up his second term as Mayor, during which he’d cleaned up the town’s notorious waterfront and red-light districts, put on a swell spread for visitors in the Lewis and Clark Exposition, and generally made of himself a thorn in the side of the beneficiaries of graft and corruption.

Os West knew he could and would win. The Republicans had nobody with his levels of visibility and reputation for honesty. So, he had traveled to P-town from his home in Salem, to remonstrate with him personally.

West arrived in Portland at the end of an inspection he’d been required to do for his job on the state railroad commission. The train didn’t reach Portland until very late, and he found the hotel full; the state Republican Party was holding its nominating convention nearby. With the help of the desk clerk, West managed to find a room in a small hotel nearby; but by the time he did, and settled into it, it was 10 p.m.

Nonetheless, he had to have a candidate by the following morning. So West picked up the telephone and rousted Harry Lane out of bed – ”informing him that, regardless of the lateness of the hour, I was coming out to his home for the purpose of discussing an important political matter,” as West put it.

Lane lived in Sellwood, which, in 1910, was more or less an adjacent town. The city streetcars would take West to the outskirts of Portland, but he was on his own for the last mile or so through the woods. It was 11 p.m. before he got there.

Lane, who received West in his night-shirt, was dubious.

”He feared,” West recalled, ”that he couldn’t make it; that he couldn’t stand the expense of such a campaign; and would have to have time to carefully consider the matter.”

Reading between the lines, it’s clear Lane was feeling discouraged. The forces of graft and vice were already celebrating his departure as mayor, and rolling back some of his reforms; and his scrupulous honesty had lost him a lot of friends among the powerful. Surrounded all the time by the state’s V.I.P.s, with whom he was unpopular, he hadn’t quite realized how popular he was among the voters at large.

West gave his best shot at convincing Lane to go for it. He told Lane to take an hour to think about it for an hour and call him at his hotel room; the party would have to have a candidate the next day.

So West traipsed through the woods and fields back to the outskirts of Portland, along the way picking up three bananas (probably from a saloon; although West didn’t drink, that was likely the only kind of business that would be open at 11:30 p.m.) to serve as a midnight snack.

”As I walked up Washington Street to my hotel, I met the adjourned Republican convention,” West wrote. ”My old friend Jay Bowerman had been nominated for governor. I leaned up against a telephone pole to watch the happy, singing delegates march by.”

Finally, around midnight, West arrived at his hotel. He wolfed down one of his bananas, crawled into bed, and lay awake there, staring at the ceiling and waiting and hoping for the phone to ring, with Dr. Harry Lane on the other end of the line.

But the telephone sat there like a sphinx on the table, all night long.

Around 1:45 a.m., West decided to take the hint. He lay there in bed and pondered deeply. There was, he knew, another candidate who might have a shot as a gubernatorial candidate. He was awfully young for the job – just 38 years old. But he had a strong reputation as an up-and-coming progressive, able to get things done, fearless and with a track record of successfully locking horns with some of the wealthiest and most powerful crooks and swindlers in the country, not once but several times. The public knew his name, and plenty of voters, both Democrats and Republicans, admired and would vote for him.

Best of all, he wouldn’t have to be pleaded with. All West had to do was make up his mind – and throw in his hat.

At around 2 a.m., West came to a decision. He jumped out of bed and looked around for writing supplies with which to draft a platform – he’d need a platform to present himself to the party with. But there was nothing in the room, and for some reason he wasn’t packing anything with him.

”So, I arose, dumped the remaining bananas out of the bag,” West recalled; ”split it down the sides; flattened it out and wrote a gubernatorial platform; crawled back into bed; cried and fell asleep.”

The platform scratched on that banana peel would carry West to a narrow victory over Bowerman a few months later. Like Harry Lane, Oswald West was widely hated by the wealthy swells of the state, and for the same reasons an honest cop is hated by the owners of illegal casinos; but his reputation as a fearless square shooter made him very popular with the voters. Lane, belatedly realizing his own popularity, was so inspired by West’s success that he stood for U.S. Senator two years later, and won the seat handily.

So in 1912, when the moment was ripe to save the beaches of the state from private development, a man was in the governor’s office who would take the necessary action – famously, declaring the beaches to be state highways and putting them under the jurisdiction of the highway department.

And in 1917, when President Woodrow Wilson went before Congress to demand that it agree to make what would arguably be the worst and most destructive mistake in the history of American government – entry into the First World War – a man was in the Senate who would, on Oregon’s behalf, vote ”no.”

And it all had its roots in a flattened banana peel plastered on the table of a small Portland hotel.

(Sources: ”Reminiscences and Anecdotes: McNarys and Lanes,” an article by Oswald West published in the September 1951 issue of Oregon Historical Quarterly; ”Oswald D. West (1873-1960),” an article by Stephen R. Mark, and ”Harry Lane (1855-1917),” an article by Kimberly Jensen, both published in The Oregon Encyclopedia, oregonencyclopedia.org).

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. His book, ”Heroes and Rascals of Old Oregon,” was recently published by Ouragan House Publishers. To contact him or suggest a topic: [email protected] or 541-357-2222.